Creator’s Rights, Karen Berger and the British Invasion, the Batman Movie, Vertigo and Milestone, More

As a follow-on to our project on the 50th Anniversary of the Direct Market (see “Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary“), we interviewed former DC Comics President and Publisher Jenette Kahn, who was hired as DC Publisher, the first woman in management at the company, at 28, and went on to remain at the company for 27 years, a period that transformed DC and the comics business. In Part 2, she talks about the battles to get creators more rights and compensation, Karen Berger and the British invasion, the Batman movie and licensing, Vertigo and Milestone, the move into books, and some final thoughts. In Part 1, she talks about how her early career starting magazines led to being hired at DC, what it was like coming into a nearly all-male company, and the early days of nurturing the Direct Market.

An ICv2 columnist wrote a column on 1986, which was such an incredible year in the comics business and especially at DC, because you had Watchmen and The Dark Knight, Killing Joke was around the same time, these incredible books that are still sold today (see “Why 1986 Stands Out“). How did things come together to create this incredible wave of hugely important books all around the same time? Was that a rights thing?

This changed in terms of our ability to attract writers and artists, and they had been bringing their most exciting ideas to us. There’s a whole change in artist’s rights.

When I came to DC, as I’m sure you know, standard industry practice was that when you went to cash your check, there was a stamp on the back where you endorsed it and you gave away all rights in perpetuity to what you have just created. It was so unjust, so unfair, but it was the industry standard.

As someone who had been on the creative side herself already and made the magazines, and knowing what it was like not to get one’s just desserts in terms of the creativity, I wanted to change that.

We did change that. We made sure, over time, that artists and writers would get the artwork back, that they would get credited in the comic books, that they would get royalties, and that, in their own creations, they would get a share of the licensing revenue, and of movies and TV.

That was the hardest one to change because we were part of a large corporation, and since there was no artist’s union at that point, no one saying, “Well, we quit unless you give us these rights,” this was really motivated solely by us. Although, of course, there was discontent among artists and writers that they didn’t have that participation.

I basically said to Bill Sarnoff, who was then the chairman of Warner Publishing, “Right now, there are artists and writers who have great ideas, but they’re not sharing with us because they’re not going to be able to participate in something they’ve created themselves, so we’re not getting those ideas.

“But wouldn’t you rather have 50 percent of those ideas rather than 0 percent, 100 percent of nothing, 100 percent of what we don’t have?” That argument carried the day. We were able to give things to the people who came in with their own brand‑new creations, to give 50 percent guaranteed, 50 percent of the merchandise, and TV and film revenue.

This changed the landscape, it changed the climate. Even though some of the most amazing books that were written in that period in the 80s were based on DC characters like Dark Knight or Killing Joke, it was still in an environment where artists and writers felt they were respected and they would be given their due.

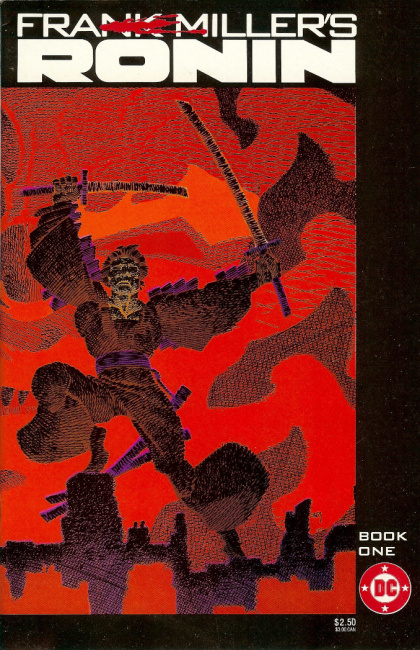

Part of it also, I think, was a dedication on our part to realize artist’s visions. (When I say artist’s input, it means the artists who draw and the artists who write, the talent.) Ronin came out of a lunch I had with Frank Miller, where I basically said, “Tell me what you want to do, and we’ll see if we can do it.”

He told me about a Ronin story; I was a huge fan of samurai movies, so I was right on board. In addition, he wanted to change the way the art was done, to have full paintings done by Lynn [Varley] that would then be separated photographically as opposed to mechanically, so it would have a true painterly look. He wanted it on very luxe papers.

I went down from lunch and talked to Paul, and he said, “Let’s see if we can make this happen,” and we did. That willingness to support an artist’s vision, we became known for that. That was really important.

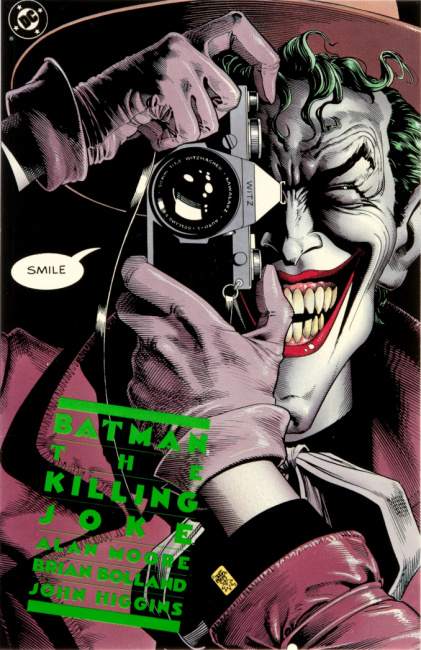

That was not just with new characters like Ronin that would be created, but we supported artist’s visions in relation to our own characters, to our tried-and-true characters, to let them take risks, to let them do very daring things. If you read The Killing Joke, The Killing Joke is brutal (although, I do believe there’s a humanist triumph in The Killing Joke, as well). We basically supported the artists and writers to take our own characters and to see them in ways that they hadn’t been seen before.

I think that whole climate, the climate of artist’s rights, the climate of support for artists, a willingness to take risks, a willingness to change production values to elevate the comics, a willingness to even turn them into books, to create graphic novels, so that these creations could sit on your bookshelf next to the best novels of the 20th century (as Watchmen was declared by Time, one of the hundred best novels). All of these factors, I think, created an environment in which we got some of the very best work from the creators.

You talked about how you brought in Frank Miller. The other person who really changed the business at the time was Alan Moore. Can you talk a little bit about how you got him to work for DC and what it was like working with him?

At one point, Paul said to me, “You know, there are all these terrific artists and writers in England. You better go check them out,” so I went.

We had a formal, crazy dinner, because I had the contact in Warner Brothers who set up the dinner, some very glitzy dinner, which wasn’t really necessary, but it was out of our hands at that moment. We met so many of the artists and writers, and we began to court them.

Then I came back with Dick Giordano and Karen Berger, and this time it was much less formal parties. I have to say, everybody had such particular accents, depending upon what part of the UK they came from. Karen and I would talk about trying to understand one person versus another as the accents changed.

Dick would just sail through these parties with the most benign expression on his face. Afterwards, we said, “How did you do it? How did you process all the different accents?” He said, “Oh, I just turned off my hearing aid and smiled.”

Yes, he was very deaf, wasn’t he?

Yes, he was. He did have hearing aids, but he was like, I’m not even going to bother trying to decipher these accents.” He probably was much more successful in navigating these parties than either Karen or I was.

In terms of Alan, right away we knew he was someone we wanted to work with. There were many other British artists and writers, but it was Karen who took it upon herself to really forge strong relationships with the British talent.

When she came back after one of these trips that we were all at together, she made a presentation to me of who the artists were, and who the writers were, and what she thought the possibilities were. I was like, “This is really great. You have earned the right to be the editor of the British invasion, and then, ultimately, anything else that fell under that.” That’s where Vertigo came about.

It really, again, owed to Karen’s own initiative in seeing the opportunity that was there, and then doing her best to show me (that she did so successfully) that she could work with these artists and writers, and make them feel comfortable, and bring them into DC, and have them do some of their best work at DC.

Karen had such a huge impact on DC and on the business. When did you realize she had that potential to change the business? It sounds like the beginning of that work with the British talent was where she really came to the fore. Is that right?

Yeah, that was the beginning with Karen. She really shined. Karen, in her low‑key way, she just showed that she was a force and has my total admiration. DC became the success that it was, it was always incredible people I worked with. As you mentioned, Paul, and Karen is yet another person. There are so many on staff, and so of course so many artists and writers they worked with, but it was, we were all on the long march together, all of us.

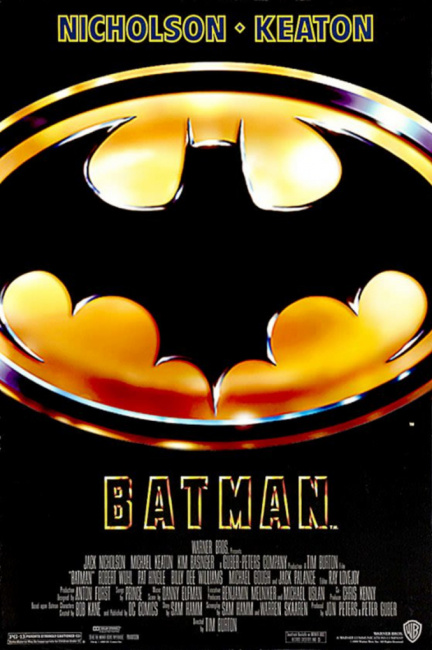

Early in your tenure, there were several Superman movies, and then in 1989 came the Tim Burton Batman movie, and that was so different from anything that had been done before. What was DC’s involvement if any, in the development of that new kind of entertainment based on comics?

In terms of the movie, we had approval rights so we were always on the sidelines. We had to approve scripts, but we thought that we were only approving Superman doesn’t smoke, or Clark Kent doesn’t smoke, that kind of thing. We took it more seriously and especially in later Superman movies that we basically turned down because we felt, like I said to Bob Daly, who was the head of the studio at the time, that if you put Superman into a bad movie, you are killing the golden goose along with the egg.

It’s not just about whether Clark Kent doesn’t smoke or not, it’s about whether it’s a good movie or not. I would much rather have been the person who’s endorsed the great movie rather than had quashed bad movie, but there was a lot of quashes going on.

The first Batman movie, all that we really had to say on that was that Mark Canton came to me and said, “How about Michael Keaton?” I was like, “I’m not sure.” He said, “No, no.” He said, “I understand why you would be nervous.” He said, “We got him a great toupee.’”

He continued his argument, that the humanness of Michael Keaton, that he could do the traumatized Bruce Wayne very well, which in fact, he did wonderfully. I signed off on that, but for the most part even though we were the rights holder, it was a much bigger sister company who was making a movie, so we often had to acquiesce.

What was DC’s licensing like in the 80s, and then how did the Batman movie change everything about comic licensing?

I think we were just a traditional licensor, and so, a huge movie like Batman with such a beloved character with such a strong artistic visual vision just made licensing different: all the products based on the first Batman movie and Tim Burton’s extraordinary vision, but not just Tim, but also the production designer, Anton Furst.

Anton, whose drawings for the Batman movie are to this day just so evocative. The look of the movie and again, a favorite character and the character done in a way that captures a true sensibility of cool. Seeing the kinds of products you might want to put out, you didn’t want to put out your Batman peanut butter, that would have seemed a little too kitsch. As the comics got more sophisticated, as the movie got more sophisticated, so did the licenses.

We remember two turning points. One was seeing [Batman star Jack] Nicholson wearing his Batman sneakers on the sideline of the Lakers game.

[laughs]

The other one was seeing Batman T‑shirts on Soul Train. That was like, “OK, the cool kids are doing this, so this is a good thing.”

[laughs] The first Batman movie was the epitome of cool. I mentioned Anton Furst. He was so influenced by an incredible architect and architectural designer named Hugh Ferriss, whose drawings are so atmospheric and poetic. Anton drew heavily on those for his vision of what Gotham would look like.

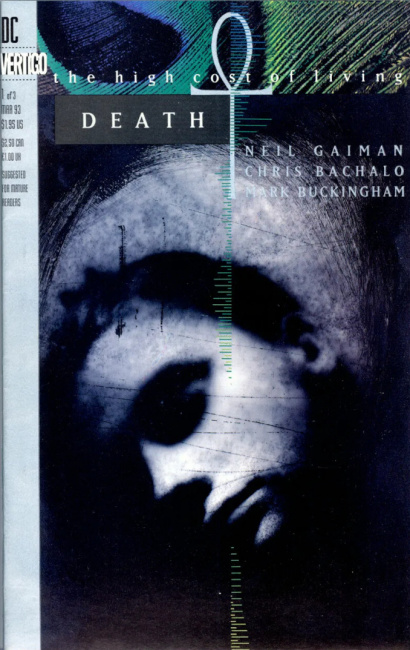

Another huge year, which you referred to previously, was 1993, when you launched Vertigo and Milestone. Let’s start with Vertigo. Why did you make the decision to launch that under a different imprint, which wasn’t really a comic publisher thing at the time?

We thought about Vertigo as a different imprint because we wanted to separate it from the superheroes’ world. The superheroes world, the DCU, had so many crossovers and collisions of characters and storylines, and was a thing unto itself. We wanted, almost, to have an indie imprint that would be very clear to creators and very clear to readers that this was not Superman’s world, this was a different world, but a really evocative, exciting one.

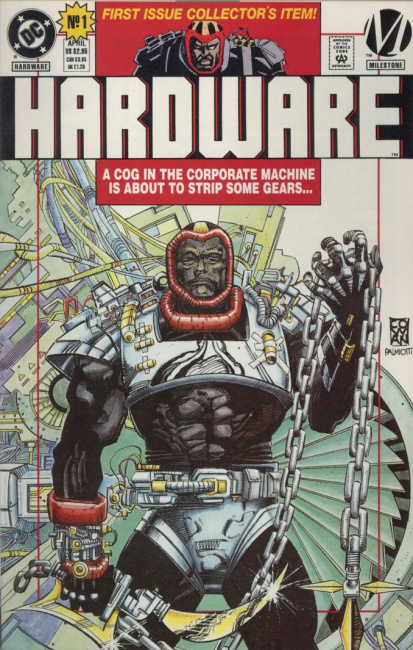

You also started Milestone in 1993. How did that come about?

We actually were approached by the creators of Milestone to work out some kind of coexistence and support, where they could do something that was radical at the time, which was to create multi‑ethnic characters created by multi‑ethnic creators.

Paul and I were so supportive of that idea. We wanted to be involved, we wanted to help. Again, props to Paul, that he worked out a business arrangement with them that they would have autonomy, but have also the strength of DC.

Then in the 90s, another huge development where DC was one of the leaders was moving heavily into the book business. Can you talk a little bit about what led to that decision to expand the book format so dramatically, and what changes did it bring?

Going back to The Dark Knight, Frank Miller said, “And when publishing Dark Knight, I want the comic to have a spine,” because as beautiful as Ronin was in its earliest iteration, it did not have a spine. Frank wanted a spine. He wanted to give the book imprimatur to his work. Again, working with production, working with Paul, looking at the economics, we figured out a way to put a spine on The Dark Knight.

That’s really where we woke up to the idea of comics as books, that these are permanent comics, that they didn’t have to be put into plastic sleeves to be saved and then, maybe, boxed and put in basements or storage rooms.

You could actually have them on your bookshelf, where you can go to them, and open them, and read them (or not open them if you didn’t want to crack the cover). It could have pride of place. We had that instinct early on. We understood it and supported it.

As time went on, I knew more and more that we should do that, that it gave comics a secondary life and a semi‑permanent life, which we felt they deserved.

It was a natural outgrowth, whether it was taking story arcs and combining them into trade paperbacks or, from the get-go, designing something to be a graphic novel in book form. We were heavily invested. As I said, it goes all the way back to The Dark Knight.

In 2002, you decided to leave DC and go into the movie business. Why did you decide it was time to move on?

I had been there for 27 years, and I loved it. I had the best job in the galaxy. I worked with the best people. I worked in such a wonderful medium. But I needed the challenge of a learning curve again. I thought, what transferable skills do I have? Not that many, but I think I know how to tell stories in pictures and words. Maybe I could be a producer?

I partnered with this wonderful partner. I’ve had so many great partners, I must say, in my creative life. Of course, I’ve mentioned Paul over and over again, and Milton Glaser on my magazine Smash was, again, the best of partners. Incredible graphic designer, artist, visionary, Milton Glaser.

Then I have this amazing partner again in Adam Richman for my partner in Double Nickel. Adam had been in the business for about seven years when we partnered. I knew nothing, really. Adam was my seeing‑eye person.

Because you were really the only woman in an executive role and changed so much of the culture at DC, how do you evaluate your role in making comics a place that was more friendly to women, both in publishing and as readers?

When I came to DC, as I mentioned, there were just two women on staff. When I left, half the staff was women, which I feel tremendously happy about. [laughs] I think so much of it came from just the fact that, if a woman could be the head of the company, then why not every other aspect of comics?

Being the head of the company, it’s just one job among many that make for great comics, that make for a great industry.

I think part of it was just by being there, and part of it also was that just as I believed in comics, just as I believed in the artists and writers, I believed that women in the industry could do anything, any role. It was always clear that nobody ever doubted that I was equally supportive of women and women’s stories as I was of anything by men.

That remains true to this day in terms of the stories that we tell at Double Nickel. They’re good stories. It doesn’t matter who writes them, who tells them because good stories have a life of their own. I’m proud to put them out, proud that we do that at DC.

We broke ground in so many ways at DC with gay characters, with multi‑ethnic characters, with the kinds of things we looked at, like gun control and landmines. Storytelling can change people’s hearts and minds. We all know that. To do that at DC for so many years, and now to do that at Double Nickel is a privilege.

We just have one more question, which is, do you still read comics?

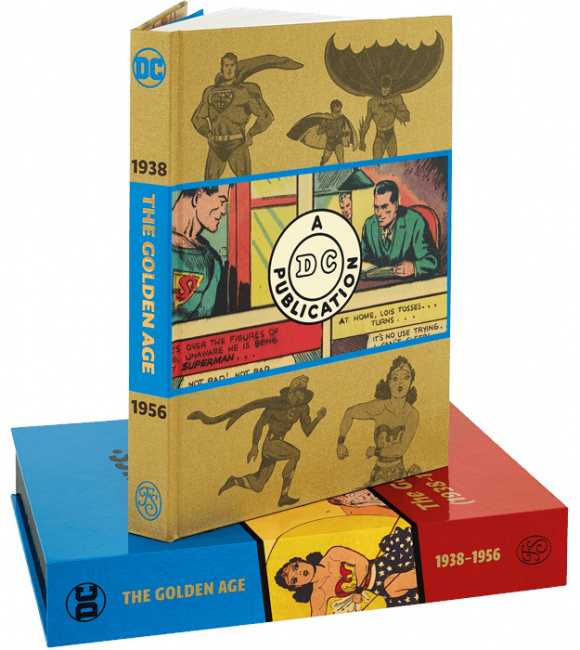

I do so much reading for Double Nickel that I don’t read comics for pleasure the way I used to. But Folio Society in the UK, which publishes really extravagant books on pop culture, has asked me to curate books on DC characters. I’ve done one on the Golden Age, and I’ve done Batman, and I’ve finished the Silver Age, and now I’m doing Superman. I am reading an awful lot of comics again in order to do these books. Yes, I’m back into it.

I have just written Mike Carlin, because I am working on Superman. I always loved the story that, when he was the editor (it was John Byrne, who wrote and drew it), it was a backup story where Turpin thinks that he should propose to Maggie.

He’s been injured in the line of duty and she’s visited him in the hospital nearly every day. He comes to her apartment building, unannounced, with flowers because he wants to declare his heart, and he discovers that she has a girlfriend.

He wants to resign and just pack up his things. He’s totally embarrassed, and he doesn’t want to embarrass her. She’s like, “No, you’re on the job. You are my guy.” It’s just such a lovely story. It’s the first gay woman in comics as far as we know, and told in such a lovely way.

I wrote to Mike, I said, I’d love to read that again. I just read it again. I was so moved by it. I thought it was wonderful. Small story, but a story so meaningful and with so much heart.

That’s the sign of a great story, right? Something that holds up over a long period of time. You can still read it again and it still moves you.

Really, truly, really truly.

Source: ICv2