This piece is part of ICv2’s year-long celebration of 50 years of the Direct Market. For more, see “Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary.”

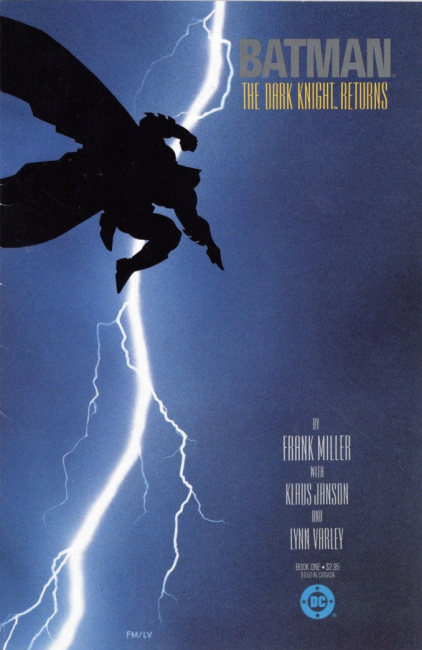

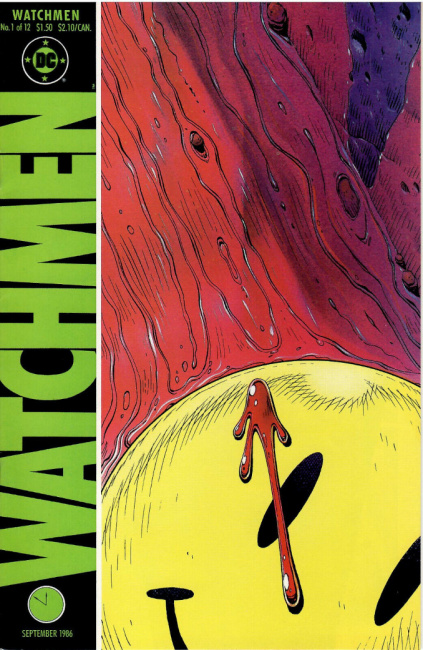

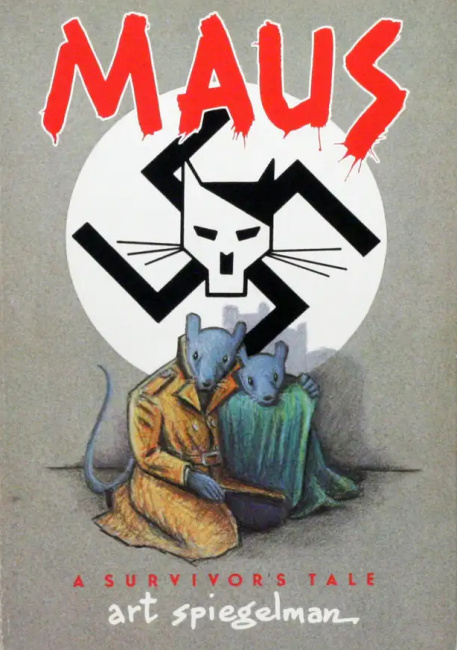

Even from a distance of nearly four decades, 1986 still stands out as a landmark year for the comics business. At the highest level, it was the year of The Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen and Maus, the “big three” that put comics on the cultural radar for the first time. But it was also the year when the Direct Market model proved that creating comics for the most devoted and discerning readers was the future of the business.

Beyond the big three. The glow of year’s top titles tends to outshine what else was going on in comics that year, which is a shame because there was an embarrassment of riches. First, consider the year’s three most celebrated auteurs, Frank Miller, Alan Moore and Art Spiegelman.

In 1986, Frank Miller gave us the classic “Born Again” arc on Daredevil, drawn by David Mazzuchelli, and another collaboration with Mazzuchelli, Batman Year One, which many people think is actually a better Batman story than TDKR. He also wrote Elektra: Assassin, featuring the white-hot art of Bill Sienkiewicz, finally presented in a quality format that showcased his multimedia experiments properly. Any other year, any of these three books would have been hailed as a singular breakthrough. In 1986, they were Frank Miller’s other projects while he did The Dark Knight Returns.

Not to be outdone, Alan Moore had a few other things on his plate while he was busy rewiring our understanding of the superhero genre. For one thing, he still had his day job writing DC’s Saga of the Swamp Thing, where he’d been blowing readers’ minds since he took over in 1982. As Watchmen ticked through its paces, Swamp Thing was embroiled in a long, creepy story arc involving everyone from Batman to John Constantine, building to a universe-altering reveal.

Moore was also recruited to write a special two-part Superman story, bidding farewell to the Silver Age version of the character. The story Moore uncorked for the occasion, “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” (drawn by Curt Swan with Murphy Anderson and George Perez), at once captures, comments on and memorializes the storytelling style that millions associated with the iconic hero, and remains one of the single greatest superhero stories ever done. In his spare time, Moore continued to grind away on Marvelman (known as Miracleman in the editions that Eclipse Comics brought out in the US). He also wrote and even drew several other strips in the UK.

Spiegelman wasn’t quite that prolific, perhaps because he had a magazine to publish. That would be RAW, the groundbreaking avant-garde art comic done in collaboration with his wife, Francoise Mouly, which presented artists like Gary Panter, Charles Burns and Jacques Tardi to American readers for the first time. RAW published its final tabloid-size issue in 1986, coming back in a more modest digest format later in the decade.

Rise of the indies. Pull the lens out further on 1986 and you’ll spot a bunch of other work drawing notice from fans and critics.

Fantagraphics Books’ Love and Rockets hit a stellar high point in 1986 with the “Death of Speedy” storyline, written and drawn by Jaime Hernandez, whose cartooning had rounded into classic form. For fans who had little use for superheroes or genre material, that was the major story of the year right there.

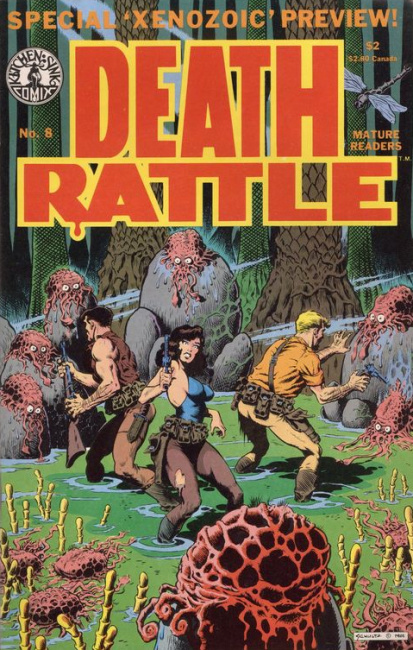

Kitchen Sink Press picked up a poignant, adult-themed funny animal strip called Omaha the Cat Dancer, by Reed Waller and Kate Worley, which became a big hit. KSP also published Will Eisner’s lightly-fictionalized graphic memoir of his early days in the comics business, The Dreamer, one of his strongest long-form works. In a year without Maus, it might have been Eisner’s work we’d be talking about as book of the year. And if you happen to pick up Death Rattle #8 in December, 1986, you might have noticed an 8-page adventure story that looked like it came straight off Al Williamson’s drawing board. That was the first installment of Xenozoic Tales, and the comics debut of Mark Schultz, who went on to establish himself as a major talent in the next decade.

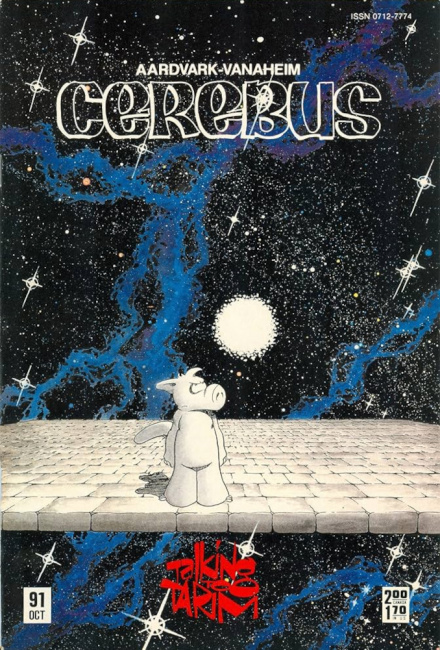

Then there was Cerebus, the long-running pioneer of independent self-published comics. In 1986, Dave Sim’s irascible aardvark had been elected Pope of Iest and was embroiled in the 4-year epic “Church and State,” a storyline that turned out to be the creative and commercial apex of the 300-issue series.

Further down the racks, you might have been tempted by Samurai Penguin #1, the first offering from Slave Labor Graphics, a new publisher from San Jose, California. Or maybe you’d take a flier on Boris the Bear by James Dean Smith, Randy Stradley and Mike Richardson, published under the imprint Richardson had just spun up, Dark Horse Comics. Later that year, a second title, Dark Horse Presents, would introduce Paul Chadwick’s Concrete.

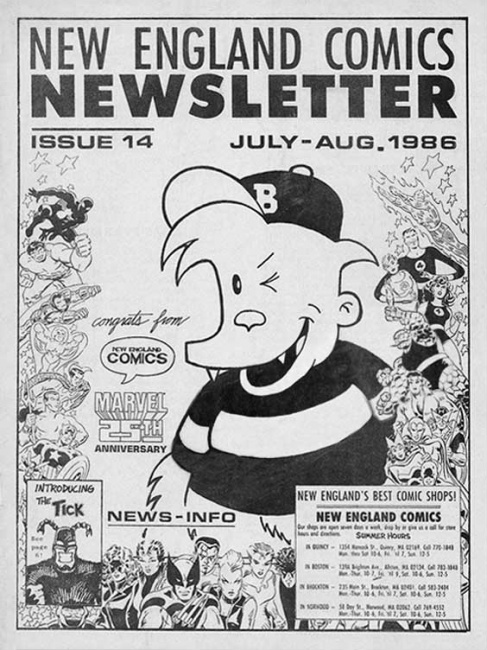

What else happened in 1986? Eighteen year-old cartoonist Ben Edlund created The Tick as a mascot for New England Comics, drawing the character’s first adventures in The New England Comics Newsletter 14-15. In London, art student Dave McKean met young journalist Neil Gaiman and the two began collaborating on Violent Cases, which would be published by Titan in 1987. Alternative weekly syndicated cartoonist Matt Groening (Life in Hell) was approached by producer James Brooks to develop animated shorts and bumpers for the Tracey Ullman Show. That project, The Simpsons, would first air in April, 1987.

Oh, and DC Comics gave us a preview of the innovations of TDKR with Howard Chaykin’s The Shadow miniseries, rebooted Superman under the creative direction of John Byrne, and set the stage for George Perez’s reinvented Wonder Woman. Marvel Comics, which lacked some of these creative highlights, cried all the way to the bank with 70% of the market on the back of its burgeoning X-Men franchise.

Everyone was young and ambitious. There were a lot of reasons that 1986 was such a landmark year, but one of the less remarked-on ones has to do with demographics. The late 70s and early 80s saw a generational change in industry management, as founding publishers and veteran editors gave way to much younger leadership.

In 1986, DC publisher Jenette Kahn, who’d been on the job since 1976, was not yet 40; her lieutenant, then-vice president Paul Levitz, turned 30 in October, and one of the company’s more important editors, Karen Berger, was still in her 20s. Marvel was under the firm control of Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter, 35, and staffed by his contemporaries. Most of the independent publishers were even younger; so were the distributors and retailers. This cohort reflected the tastes and values of their customers because they came out of the same culture, with the same ambitions to expand comics beyond their previous limits – and were at a stage of their careers where they were willing to take chances.

Today, a lot of the industry has aged in place, or the new crop of unruly risk-takers has been hemmed in by corporate management. If you want to look for the next 1986 in comics, look for the younger faces, if you can find them.

Looking back with envy. The Direct Market created a cozy circle of production, distribution and consumption that eventually closed around the throat of the industry, creating severe problems that linger on to the present day. But in 1986, it was an exciting and unprecedented convergence of talent, interests, passion and money. The resulting explosion of creative energy was almost inevitable.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture and an Eisner-Award nominee.

Source: ICv2