For this part of the history of the Direct Market, we are turning the tables and letting comics historian Dan Gearino, writer of Comic Shop: The Retail Mavericks Who Gave Us a New Geek Culture, interview ICv2 CEO Milton Griepp about his days at the helm of Capital City Distribution. Griepp and his partner John Davis started Capital City in 1980, and it grew from, literally, two guys and a truck to become the largest comics distributor in the U.S. Part 1 focuses on Griepp’s early days working for a Wisconsin distributor of alternative papers and underground comics that was swallowed up by a larger distributor with a very different culture and ultimately went bankrupt, leaving him and Davis to strike out on their own and create Capital City. In Part 2, Griepp discusses Capital City’s years of growth, as it adapted to a changing market and introduced innovative practices to comics distribution. And in Part 3, Griepp talks about Marvel’s decision to self-distribute and the chain reaction that started, which ultimately led him and Davis to sell Capital City to Diamond in 1996.

To watch a video of this interview, see “ICv2 Video Interview – Milton Griepp, Part 1.”

This interview and article are part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see “Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary.”

Dan Gearino:

I’m pleased to be here today with Milton Griepp, who has lived much of the history of the Direct Market and was a key player in a lot of it. How are you, Milton?

Milton Griepp: I’m great, thanks.

Let’s start by defining some terms. The term “Direct Market” gets thrown around a lot, but some people don’t know what that means. When we say “Direct Market,” what are we talking about?

The name comes from the history of how this part of the business was created. “Direct” was used as the name because it was different from the less direct method of distribution that took place before it. Before the Direct Market, comics were sold from publishers to national distributors to local wholesalers to retailers. To the extent that comic stores were able to get comics through that network, they had to buy from those local wholesalers who typically knew nothing about comics, may have been corrupt, and weren’t very good at distributing comics.

The “direct” part of the name comes from the fact that when Phil Seuling approached a comic publisher, the comic publisher sold direct to a comic distributor who sold to a comic store. It cut out a layer of distribution, it was a more direct form of distribution, and so it came to be called the Direct Market.

As we’ll get to in a little bit, there’s a bunch of steps in the evolution of that process that you were right there for, but I want to go back earlier than that. Tell me, where were you born, and where did you grow up?

I was born and grew up in a town called Shawano, Wisconsin, which was primarily an agricultural community in north central Wisconsin.

Your entry onto this path that would send you into comics was, I believe, working for WIND in Madison, correct? How do we get from growing up in that town in Wisconsin to working for this distributor in Madison?

I came to the University of Wisconsin in Madison in 1971 with a close friend from school in Shawano High School. We roomed together our sophomore year. He was a comic collector and an aspiring comic dealer, and I started going to conventions with him.

I met a guy at a job I was working at driving forklift for a mail order company called Swiss Colony, which is still around. They sell cheese and sausage packages for the holidays and so on. He said that another job he was working at had a position open for somebody that knew something about comics. He knew that I’d been to a couple of comic shows.

I ended up getting hired by WIND because of that limited knowledge of the comics business from going to conventions and being involved a little bit in my friend’s comic dealing.

Just so we can get a timeline here, what year was that that you started to work for WIND?

That was 1976.

What did WIND stand for? Give me a sense of the personality of this company.

It stood for Wisconsin Independent News Distributors. It was a political group, one of a bunch in Madison at that time. There was a book co‑op that sold books down in the university area. There were food co‑ops. There was a distribution company that served food co‑ops.

WIND was formed to handle the periodicals and books and newspapers associated with that movement and sell them to locations like food co‑ops, record stores, head shops, and then over time evolved into selling more into traditional outlets like newsstands.

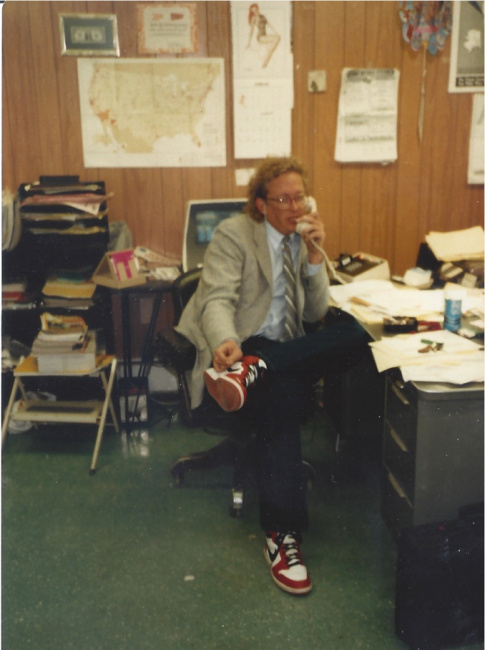

If I was to meet you back then, how would you describe yourself during your WIND days?

I was a sociology grad student when I started. It was a part‑time job that I was just using to earn money to work my way through grad school. I was a big fan of the underground comics. That was primarily what I read, although I was also reading Marvels, which had sort of a subversive feel at that time. I enjoyed the stuff we were selling.

I wasn’t as involved in politics as a lot of the people in that business. I certainly went to the war protests in Madison and was involved in more peripheral ways rather than being an organizer or a key figure in any kind of political movement.

If there was an employee photo back then, would’ve this been a bunch of obvious kind of hippie types? Were you more strait‑laced? Would you have blended right in, in terms of how you look?

I think I blended right in.

What did a hippie, circa that era, look like?

Males had long hair, and clothes were jeans, tie‑dye, that kind of stuff.

What was your sense of WIND as a business? Did you walk in and think, “This is really well‑run. This is going to last a long time”? What were your impressions?

It was organized as a collective, meaning, it was collective decision‑making, trying to reach consensus, and that was not a great way to run a business. So no, I didn’t think it was particularly well‑run, although the people that had the most responsible positions were very knowledgeable about the book and magazine business. They were super smart people. It wasn’t that anybody didn’t understand what the business was like. They just had different goals, not purely business goals, in terms of what they were trying to accomplish.

How does WIND evolve into what came next? How did that work?

As I said, that wasn’t a great way to run a business, and [WIND] was losing money, ran out of money. Eventually, as the company, WIND, was dissolving, all of the senior people disappeared. I ended up being made president, because I was the last person standing, and handled the bankruptcy. The company went through bankruptcy.

As a result of that, one of our suppliers (the company we’d been buying color comics from, Marvel Comics and DC Comics, called Big Rapids Distribution Company) moved into Wisconsin, opened a local warehouse, and began servicing the accounts that WIND was no longer servicing. They had very similar product lines. The top products for those companies were things like High Times, Rolling Stone, National Lampoon, Mother Earth News, CoEvolution Quarterly. They carried a lot of trade books and also some more general interest magazines. We were carrying a line of computer magazines, because they weren’t generally available on the newsstands and there was a market for them in the stores that we serviced.

So they opened. They hired me and John Davis, who I’d hired at WIND, and several other people from the WIND crew to operate it.

In terms of the timeline, what year is it that you became a Big Rapids employee? From what year to what year was that?

That was ’78 to early ’80.

Big Rapids is a somewhat significant company in the history of the direct market, or an interesting bridge between the very early direct market and what would come later. I’m wondering if you could describe what’s the personality of that company. What were your impressions of them?

That was super educational in a lot of ways. For one thing, they definitely had a harder edge. It was a political group, but they were based in Detroit and operated in a different kind of environment than you’d find in a college town in Wisconsin.

They also were attempting to expand into competition directly with the local ID [independent] wholesaler. That meant they were trying to carry a full line of magazines, mass‑market paperbacks, trade books. That kind of competition was a different situation because Ludington News, which was the ID wholesaler in Detroit at the time, was a tough organization. The Teamsters were their union. They didn’t like Big Rapids because it was a nonunion shop also organized as a collective or a co‑op. The personality was tougher, and they operated in a tougher environment.

That competition with ID wholesalers was a big part of what made them who they were because that was just a different world. It wasn’t selling to hippies in head shops. It was selling to party stores in Detroit and trying to get them to buy from Big Rapids instead of Ludington.

What’s the wildest thing you saw a Big Rapids person do in a competitive context?

I went once or twice down to Hammond News. Hammond News was a renegade ID located in the far south suburbs of Chicago. They had these things called cash routes, which they’d have drivers come in, buy magazines, pay cash for them, and they didn’t care where they went, and they didn’t adhere to the regional monopolies that most of the ID wholesalers did.

Visiting that was a very interesting situation. They’d come in with an envelope of cash and a stack of magazine covers for returns and then haul out magazines. That was interesting. In terms of things that Big Rapids did, they took a different approach to collecting money because of their history and environment. I heard about them holding a store owner that wouldn’t pay (this wasn’t a comic store owner, like a newsstand owner) out of a second story window to try to convince him that it was time to pay his bill.

John and I were the comic experts. We weren’t expected to do that kind of stuff, but we were the experts on the materials. For example, Jim Friel, who was an early comic distributor in Michigan owed Big Rapids money and he was having trouble paying. They had John and I come into Michigan, and they took us and some of their heavies out to see Friel. The goal was to either gather up inventory to offset what he owed or collect the money in some way. We walked in and this guy Pete Kwant, who was one of Jim Kennedy’s lieutenants, saw a copy of Star Wars #1, picked it up, ripped it in half and said, “Half price sale.” That was the beginning of that interaction.

Was Jim Kennedy the owner or what was his official role within this company?

I don’t even remember his title. It might have been general manager or something like that. No, there were no owners. Like I said, it was organized and I never saw their organization papers, but it’s some kind of collective or co‑op membership organization. He ran it. That was undisputed.

I found that to be a company that is really difficult to get any sort of records on. Jim is a very difficult person to get any sort of substantial biographical information on. What was he like? When you were just one on one with Jim Kennedy, how would you describe his manner?

Oh, he was super smart. He was short but had a very deep voice. He commanded a room. He was charismatic. He drank a lot. Big Rapids was a very heavy drinking organization, which was my scene at the time as well. They had a cooler of beer in the office, and late in the day employees would be having a few.

His ability in a room to interact with people and effect change was dramatic. He was a strong leader. They’d have these company meetings where they got everybody together to talk about the future of the company, and he was a commanding figure in those meetings.

In terms of running an effective business, at what point did you get a sense that there were some issues with how things were run?

The comics business with Big Rapids has a checkered past because it grew out of the Donahoe Brothers comic distribution business. Donahoe Brothers were very early. They used to claim that the Donahoe brothers bought from Marvel before Phil did. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but it was definitely around the same time.

They didn’t last long. They didn’t pay the publishers, and Big Rapids ended up taking over their accounts and some of their suppliers. I don’t know how that happened. That was before they moved into Wisconsin or before I started doing business with them.

John and I were dealing with fanzine publishers and underground comic publishers and companies that we’d done business with at WIND, and we kept running into companies that they [Big Rapids] weren’t paying on time. Also in ’79 I was involved in a trip to New York. I remember we went to see Marvel Comics and so we met with the Circulation Vice President Ed Shukin. Barry Kaplan (who was the, they didn’t call them CFOs then, he was like the Chief Accounting Officer or whatever) was expecting Kennedy to drop by and drop off a check; he just didn’t stop by at the end. There were people trying to collect money. I definitely had the impression that Big Rapids was not paying its bills on time. That was troubling because we’d grown to be friendly with a lot of these companies that they were having trouble with. It wasn’t a good situation.

Big Rapids was a company that just could not continue at some point. What was the end of Big Rapids like, and then what did you do?

I want to give you some idea of the scale of Big Rapids, because at one point it was the largest direct comic distributor. The way that they got to be that way was not only through opening warehouses in the Midwest but also through selling to sub-distributors and drop shipping. Comics would go directly from the printer to a sub-distributor in some part of the country. Big Rapids would theoretically collect the money from them. They had trouble collecting from some of those companies.

Windy City Circulating Company was a direct distributor, in the sense that they bought through that network based in Chicago. They were very large. We did that same kind of visit where they took John and I to evaluate the inventory and Big Rapids loaded a bunch of their inventory into trucks to try to defray the debt that Windy City owed them.

[Big Rapids was] a large company and sold a lot of comic books. The end was when the cash flow was not sufficient to pay their bills, either because they weren’t getting paid or because they were spending more on expenses than they had in margin. This was pre‑computers, so it was adding machines and hand ledgers, and they did have staff that did that kind of thing, but they just did not manage in a way that made it profitable or managed their cash flow appropriately.

I remember on a trip to Detroit, Kennedy did some of his business in bars, so he would go to a bar with some of his lieutenants, a stack of dimes, his accountant’s number, and his attorney’s number. Then he’d talk to suppliers and have drinks while he was doing all that. The drinking wasn’t because he didn’t care or whatever, it was more, he drank all the time, so that was just how he rolled.

The end of it was not pretty. Basically, they got cut off from their suppliers. At that point, John and I, we no longer had jobs. We started drawing unemployment (this was early 1980), and tried to figure out what to do next.

When Big Rapids suddenly is no longer able to serve its customers, how big is that? At that point, would they have been the second biggest distributor in the country, the fifth biggest? What was their scope relative to the market as a whole?

They were either the biggest or second largest at the time when they went out of business. I remember, I have the number in my notes somewhere, I think was $300,000, $400,000 they owed Marvel. It was a good chunk of change.

While they started in Detroit and grew from the Midwest, they had a pretty large footprint because of sub‑distributors by the time they stopped serving their customers.

Yeah, it was nationwide.

You guys have this knowledge of who these customers were and knowledge of comics, and Big Rapids is gone. I say “you guys,” I mean John Davis and you, your friend and colleague. Walk me through what happened then.

I was living in a garret in a student neighborhood, a third‑floor flat, where the ceilings are only tall in the middle of the room because the roof slants.

I remember this very clearly because it was a key moment in my life. John came up. We sat down in the kitchen. He’s going, “Hey, I think we can start a little something, maybe get off unemployment. I think there’s some stores that will buy from us.”

He mentioned Bruce Ayres of Capital City Comics here in Madison that wanted to be involved. We knew some customers that we’d been selling to. If we could arrange supply, we could probably maybe make enough money to support the two of us. That was the beginning of Capital City Distribution.

You decide you’re going to do this. What do you do then? What are the first couple steps toward turning this into a reality?

We had to form a company and do all that kind of stuff, which we didn’t know much about, but we muddled our way through and did fine with it. Then we had to get supply.

One of the first calls was to Russ Ernst of Glenwood Distributors. He was based in Collinsville, Illinois and was a direct distributor at the time. He had business all over the country because he was located near the printer in Sparta, Illinois, that was printing almost all of the comics in the country at that point. We needed to source comics from him.

I believe it was right at the beginning, we also reached out to Marvel. Mike Friedrich was there, who I’d known and John had known from his time at Star*Reach because WIND bought from Star*Reach and Big Rapids did as well. That was his independent comic publisher. He became the Marvel direct sales rep. He was instrumental in getting us a direct account.

We may have bought Marvels a few months from Glenwood before we went direct with Marvel, but it was pretty early. Their terms required that you had to prepay the first month or two of comics, and after that, you could get credit. We needed $10,000. We didn’t have anything like that kind of money. We were on unemployment and really no assets.

I went to my folks, who had a dairy farm. They had a line of credit secured by their assets, including their dairy herd, with a local–it was called Production Credit Association—it was basically agricultural lending, asset‑based agricultural lending. They took out a $10,000 loan, loaned it to us, and we used that to pay our first Marvel down payment, that initial prepayment. Then, eventually we were able to pay them back once we got credit from Marvel and we were getting paid from our customers.

We did the same thing when we had to go direct to DC a little while later, borrowed money from them and used it for the prepayment, and then paid them off as we were able to get credit from the suppliers.

I’m interested in the early stages of when a company like this gets started. You’re securing contracts and relationships with your suppliers. You also have to build this infrastructure just to be able to do the basics of serving your customers. I presume you and John couldn’t do that all by yourselves. How do you do that?

We actually did do it all ourselves.

We needed legal and accounting infrastructure. We didn’t know how to do that, so we called the local bar association, and they picked the name that came up to the top of their list and said, “Here’s a local attorney that can help you with business formation.” That attorney is still my business attorney today, so a very long‑term relationship. We also needed an accountant, same kind of thing. I don’t remember. We found a CPA through a similar referral. They helped us set up our books. We didn’t know what a chart of account was, or any of the bookkeeping. He showed us how to set up bookkeeping, which, at the time, was on ledgers, handwritten ledgers.

Then, really, it was keeping track of the orders, packing the books, and shipping them.

Keeping track of the orders was done on spreadsheets. This isn’t an Excel spreadsheet. This is a piece of paper with boxes on it. Each month’s comics, we’d send out a list of the comics that were coming out. Our customers would send back quantities for those comics.

Then, for things that weren’t comics, we had things called standing draws. That was a term that came from the magazine business. A draw was how many copies a store took from a wholesaler. They might have a draw of 50 copies of TV Guide and get 50 copies of TV Guide every issue. It was the same every issue.

So on things like—what were some of the early magazines—Comic Reader, I think, was around then—they’d just give us a draw: “We want 25 of each.” Our order form consisted of one piece of paper that fit all of the monthly releases on it for comic books. The total information we had was the title, the price, the writer, and the artist.

The Marvels would fit in one column. The DCs didn’t take up the whole rest of the column, so we had Warrens at the bottom of the column with DCs. That side of the sheet was the order form for comics.

Then we had a standing draw form, which they could fill out once and we’d keep sending the same number every month. If they wanted to change, they’d do that. Eventually, that had to go into monthly orders to accommodate changes more readily. At the beginning, everything was standing draw except for color comics.

Then, when they came in, we’d invoice, hand invoice, and pack the boxes and ship them.

So there was a single piece of paper or several pieces of paper that basically contained the core information for what all of your customers were buying.

That’s right.

I suppose you didn’t want to lose that piece of paper. That would have been bad.

Right.

Were you guys driving the truck to make deliveries? It’s two guys initially. Were you hiring people to do that stuff?

We did drive the trucks. Mostly, John did the Madison deliveries, and I did the Milwaukee deliveries. He did some of those in his car. We also bought a step van, which is like a delivery truck kind of vehicle that WIND had owned. It was this gray, old, beat-up vehicle. You could see through the floor to the highway below, and it had bullet holes in the side, because there was a guy at WIND who was heavy into supporting the IRA and he’d taken it out with some friends and was using it for target practice at one point. It was an interesting vehicle, but I’d drive that to Milwaukee and do the deliveries there. John would take his car down to downtown in Madison or around to the stores and deliver here.

Click here for Part 2.

Source: ICv2