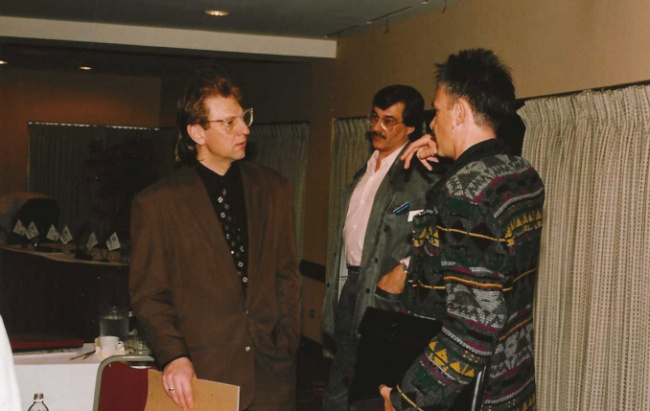

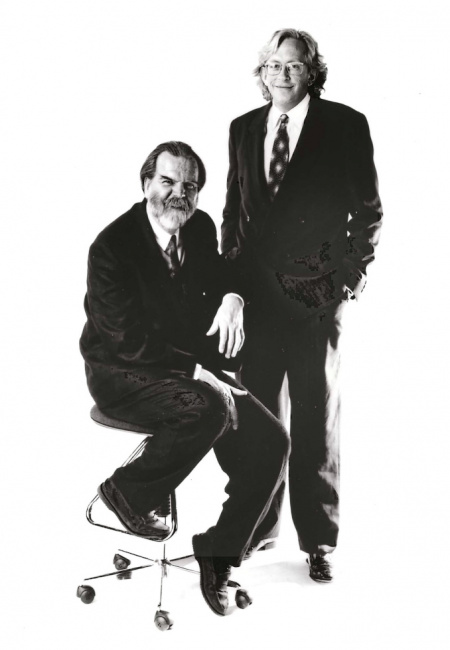

John Davis and Milton Griepp in a portrait for their ‘Distribution Professionals’ ad campaign, mid-80s.

On a frigid evening in 1980, John Davis visited the apartment of Milton Griepp, hoping that his friend and recent co-worker would listen to a business proposition.

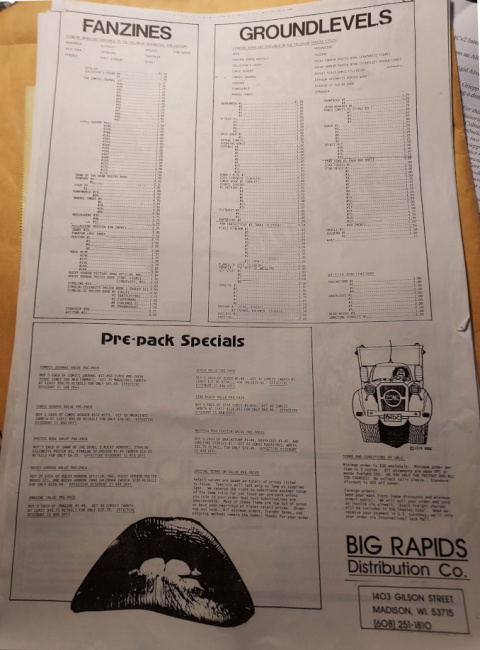

Both men were living on government assistance after the collapse of their employer, Big Rapids Distribution of Detroit, one of the largest comic book distribution companies in the country.

Davis believed that the sudden departure of Big Rapids had left a void in the market that somebody needed to step up to fill. He and Griepp talked into the night and hatched a plan for how they, just two guys in Madison, Wisconsin, could do it.

The resulting business, Capital City Distribution, grew to be the largest comic book distributor in the country, an innovator that helped to foster rapid growth in the number and size of comic book stores. And then, after a decade-plus of growth, Capital City went through a swift decline, the result of decisions by the major comics publishers, Marvel Comics and DC Comics, and the ascendancy of a rival distributor, Diamond Comic Distributors.

For Davis, Griepp and some of the earliest employees at Capital City, the company’s rise is filled with warm memories of camaraderie and entrepreneurial savvy. And the company’s fall, even though it was decades ago, still inspires sadness and what-ifs.

Prehistory, with WIND and Big Rapids

Madison in the 1970s was a bastion of hippie culture that acted as a magnet for young people who grew up in much more conservative communities across the state.

Griepp, a recent graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, got a job in 1976 at Wisconsin Independent News Distributors, or WIND. The company was a cooperatively owned distributor of books and magazines. Much of its inventory was tied to the counterculture, like High Times and Mother Earth News magazines.

The company started distributing comic books and the long-haired Griepp, whose main qualification was that he liked comics, oversaw this area.

“It was a part‑time job that I was just using to earn money to work my way through grad school,” said Griepp, who was studying sociology. “I was a big fan of the underground comics. That was primarily what I read, although I was also reading Marvels, which had a subversive feel at that time. I enjoyed the stuff we were selling.”

Davis applied for a job at WIND and that’s where he met Griepp. Davis was a recent graduate student who played in a local blues band and had been publisher of a film studies journal.

The two became friends and they also could see severe mismanagement at WIND. The company had almost no discipline handling the basics of running a business.

“It was a great year, a great place to work, I will say that—but doomed,” Davis said.

When WIND dissolved, it owed money to its comics supplier, Big Rapids of Detroit. Rather than lose those sales, Big Rapids opened a Madison office and hired Griepp and Davis to run it and service comic book stores in the region.

While WIND was kind and fun, Big Rapids had a sharp edge. This was even though both companies considered themselves part of a left-wing culture.

“They were a gangster organization,” Davis said of Big Rapids. “They were very hardcore. They carried guns. They were not afraid of physical confrontation at all.”

Some of Big Rapids’ identity came from its leader, Jim Kennedy, and some came from the intense and sometimes dirty competition among Detroit-area distributors.

Davis recalls being ordered to go along on a “raid” of a comic distributor who was behind on his bills. The crew entered the shop, along with a German shepherd dog, and they took comics and other products off the shelves to cover the unpaid tab. He remembers one of the other Big Rapids people unbagging a copy of Star Wars #1, ripping it down the middle and saying, “Star Wars. Half off.”

Griepp and Davis were appalled by some of the people they worked with, but at the same time they were able to run their region as they saw fit.

“They were a large company and sold a lot of comic books,” Griepp said.

The company was able to accelerate its growth by working with sub-distributors in new regions. It was a model that could have worked if not for Big Rapids’ poor financial management.

“The end was when the cash flow was not sufficient to pay their bills either because they weren’t getting paid or because they were spending more on expenses than they had in margin,” Griepp said.

Big Rapids stopped paying its suppliers, which led to it being cut off from shipments of new products. The company went out of business at the beginning of 1980.

Within months, Davis had convinced Griepp that the two of them should start the company that would become Capital City.

‘Flying By the Seat of Our Pants’

Davis and Griepp had a head start in building their business because their work at WIND and Big Rapids had allowed them to meet comics publishers and retailers.

One of their first tasks was to get Marvel Comics, the leading publisher, to agree to become a vendor. Mike Friedrich, who was Marvel’s Direct Sales Manager, said he would do it if Capital City could provide up-front money with the initial orders.

The co-founders got this money by getting a loan from Griepp’s parents, who drew on their farm’s credit line, using the cattle on their farm as collateral.

They were able to get much of their remaining initial supply from another distributor, Glenwood Distribution, but soon opened direct accounts with other publishers. Once the company had secured a supply of comics from Marvel, DC and others, it was easy to get retailers to sign up to buy comics. Davis and Griepp went to several dozen of the retailers who were their customers at Big Rapids.

They rented a small warehouse with one loading bay and a balcony office.

Davis and Griepp did nearly all of the work themselves. They took orders, unpacked shipments from the printer, packed shipments for stores and then drove the routes to deliver comics to the stores.

They worked well together. Davis, who was in his mid-30s, had a calm presence that was well-suited to interacting with vendors and customers. Griepp, who was about a decade younger, had an aptitude for business strategy and structure.

{IMAGE_3}At about the one-year mark, Tom Flinn became the first employee who was not a co-owner. He had played in a band with Davis, and needed a job at about the time that Capital City needed another set of hands. Flinn’s job included the same mix of unpacking and packing, along with janitorial tasks like sweeping out the warehouse.

“It was a great sense of satisfaction when those undifferentiated pallets of stuff came in, and then you packed them up into orders and sent them all out,” Flinn said.

The business was growing, but it was still small enough that a late payment from a retailer or some other short-term financial issue would make the co-owners advise him not to try to deposit his paycheck for a few days.

Another early employee was Michael Martens, who had a background in local theater and skills with carpentry.

“We were pretty much flying by the seat of our pants in those days,” Martens said. “We would come across a situation we had never seen before, and we would have to figure out how to deal with it.”

As the company grew, Flinn began to focus on purchasing non-comics products from vendors, which could include posters, books or anything else. Martens became the customer service manager, handling calls from shop owners and fixing errors that came up in deliveries.

The co-owners also took on new roles to respond to growth. Griepp oversaw finances and strategy. Davis focused on purchasing comics and on serving as the company’s main emissary at trade shows and when dealing with major vendors and retailers.

Capital City was one of more than a dozen comics distributors in the country. Its competitors included Sea Gate of New York, which had been the first to sell mainstream comics directly to comic shops in 1973, Pacific Comics of San Diego and New Media/Irjax of Florida, among others.

Capital City sought to distinguish itself by offering a wide variety of products to its stores, including underground and foreign comics. The company also briefly published some of its own comics, like Nexus by Mike Baron and Steve Rude, a science fiction superhero story that helped to start long careers for both creators.

The company continued to grow, becoming by the mid-1980s the largest comics distributor in the Midwest and then expanding into other regions. This expansion meant that Capital City was moving into territory with other major distributors, leading to intense competition to get stores to sign up, and to take business away from other distributors.

The West Coast and Arizona were two of the hotly contested areas. Capital City went head to head with Bud Plant Inc. of California, a company that had taken over Pacific Comics’ distribution business.

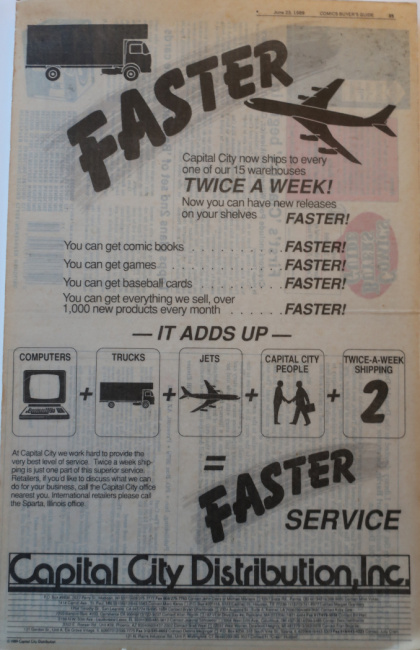

In the battle to win new store accounts and to better serve its existing accounts, Capital City began to fly new comics from St. Louis to the West Coast, rather than use ground shipping. This meant Capital City’s stores would get its products sooner than those served by other distributors. (Comics were coming from St. Louis because that was the major airport closest to the printing plant in Sparta, Illinois.)

People call this period the “Air Freight Wars,” in which Bud Plant and others began to use air service to match what Capital City had done.

Plant, the owner of Bud Plant Inc., felt burned by Capital City’s use of air freight because he thought that the distributors had agreed to limit their use of the practice because it didn’t make sense financially.

Griepp disagrees that there was any official or unofficial deal on air freight, and adds that such a deal would have been collusion, which is illegal. He also disagrees with the idea that air freight was a money-loser. Capital City had been able to make a deal with the airline TWA that kept costs low enough to be justifiable, he said.

Regardless of the specifics, this episode contributed to Plant distrusting Griepp and Capital City, which would be important a few years later when Plant was ready to sell his business.

At the beginning of 1988, Capital City was the country’s largest distributor serving comic book shops. It had grown from the two co-owners in a one-bay warehouse to more than 100 employees and more than a dozen warehouses.

The next-largest distributor was Diamond, based in Baltimore, which had started in 1982 with the purchase of assets from New Media/Irjax and had grown with a footprint mostly on the East Coast. Diamond’s owner, Steve Geppi, had made a successful transition from owning a chain of comic shops to running a distribution business.

Bud Plant Inc. was also a major player and was likely the third largest by revenue.

But the top of this heap was about to get reshuffled. Plant, who had started out as a mail-order retailer, was getting tired of the high risks of comics distribution and wanted to go back to focusing on mail order.

He decided to sell his business. Because of his rivalry with Capital City on the West Coast and his distrust of the company’s leaders, he didn’t feel comfortable approaching them about a potential sale.

At the same time, Plant trusted that he could discuss a sale with Diamond and Geppi.

That year, Diamond bought out the distribution assets of Bud Plant Inc. and then leapfrogged Capital City to become the largest comics distributor in the country.

“That was a great deal for him, and he should get credit for it,” Griepp said of Geppi.

At the moment, Griepp didn’t appreciate the full implications of the deal, but they would become clear. Capital City went on to have several of its most successful years, but Diamond’s ascendancy into a nationwide rival would turn out to be a key factor in Capital City’s undoing.

Growth and Culture Change

The late-1980s and early 1990s were a high-water mark for Capital City and the comics industry. The 1989 Batman movie had contributed to a surge in comics sales and Capital City was among the leaders in distributing Batman-themed apparel and other non-comic merchandise to stores.

In the early 1990s, comics sales soared with the release of some high-profile titles and growth in collectors buying large numbers of copies in the hope of one day making money on resale.

Capital City helped to facilitate the industry’s growth and benefited from it. In the process, the company has grown to the point that some longtime employees found it unrecognizable.

Martens said the company’s culture shift had become clear in 1992 when it moved into a newly built office building on the outskirts of Madison. He acknowledges that Capital City had outgrown its previous space, but he thinks the new building combined with the company’s large size had underscored to him that he was working for a corporation as opposed to having fun with his friends.

“The perception was that we need to take this to the next level,” he said.

To do that, the company had to hire new managers who had little background in comics, and had to tighten up its processes to a point that felt like rigidity to some of the longtime employees.

“It might have been the downfall of the company,” he said.

He wasn’t speaking in a business sense. Capital City was doing fine financially. He was talking about the company’s ability to hold onto its identity.

He left Capital City in 1994 for a job doing retailer relations for Dark Horse Comics in the Portland, Oregon, area. He remains in touch with Griepp and Davis, and feels a fondness for Capital City’s early days.

“Milton and John were the best bosses I ever had,” he said.

Flinn said the change in the company culture had to happen, even though he missed the early days. He remembers that Griepp had too many employees directly reporting to him, and, as the company needed ever-larger lines of credit from banks, the banks insisted on more of a conventional management structure.

“They were all MBA types,” Flinn said, referring to people who had master’s degrees in business administration that the company had hired.

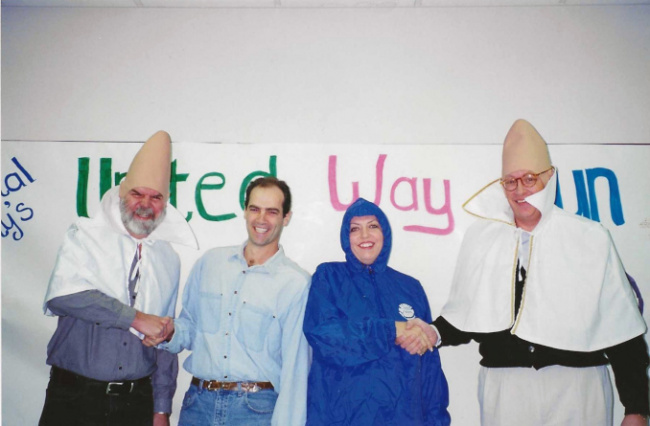

John Davis and Milton Griepp as coneheads at an employee event promoting the Capital City United Way campaign, with VP-Finance Pat Liegel and SVP-Sales and Marketing Connie Koury.

Griepp said the company needed to change to manage its growth, and he is proud of how Capital City was able to hire experts to manage finances and deploy systems to manage inventory.

When asked whether the company had lost some its identity along the way, he said this:

“One of the big things I came to understand as the person running the company is that every action I took was important,” he said. “Somebody was always watching and interpreting what I was doing, and applying it to their own jobs and how they interacted with people. If I did something that showed disrespect for a customer or disrespect for an employee, that would come back and it would be felt in the culture. I had to manage how I interacted with people in every instance, so that the people around me could take the right example from that.”

He realizes that the company’s growth made him need to be more rigid.

“In a way that was difficult because it meant distancing myself on a personal basis from friends, but it was necessary because otherwise the company would not have been able to function as a business,” he said.

Heroes World and the Beginning of the End

In 1994, the comics industry had come off the heights of its boom. Retailers that had overextended themselves during the good times now faced a financial reckoning.

Management at Marvel looked at the market and chose to focus on what it saw as inefficiencies in the market structure, rather than the decline in the quality of the company’s comics.

Marvel, which was publicly traded and run by people with little background in comics, decided that it could become more profitable by owning the company that distributed its products to comic shops. To do this, Marvel purchased Heroes World, a small distributor based in New Jersey.

The public announcement of the Heroes World deal was on December 28, 1994. Any comic shop that wanted to sell Marvel products would need to get an account with Heroes World.

With this change, Capital City, Diamond and other distributors lost the vendor that accounted for roughly 40 percent of comics sales.

In response to Marvel’s decision, DC wanted to find its own exclusive distribution partner. The company surveyed the market landscape and determined that Diamond was a better fit than Capital City.

By mid-1995, Capital City had lost its two largest suppliers, Marvel Comics and DC Comics. The business was, in effect, decimated.

Griepp and Davis scrambled to close warehouses and shrink the company’s costs to match the decrease in revenue. They also sued Marvel and DC and eventually got settlements from both.

In 1996, Capital City agreed to be purchased by Diamond Comic Distrbutors. Davis, Flinn and others from Capital City went on to work for Diamond. Griepp served as a consultant to Diamond for a while, and soon started the business that would become ICv2.

Some of the retailers who were longtime Capital City customers have said they feel like the industry took a wrong turn when Diamond emerged as the sole major distributor. Their argument is that competition between distributors was good, and the industry was worse off without Capital City’s affinity for serving customers and selling a wide variety of material. Griepp agrees with this view up to a point, but he thinks it doesn’t recognize all that Geppi and Diamond did to hold the industry together during some difficult times.

“Diamond’s been successful for decades since,” Griepp said. “You can’t say they were a bad company or weren’t good at what they were doing because businesses don’t survive unless they’re good at what they’re doing. From that perspective, it certainly wasn’t a disaster for the comics industry. Steve’s heart is totally in the place of wanting a successful comics industry.”

Asked about Capital City’s legacy, Davis said he is proud to have been part of a company that broadened the idea of what a comic shop could be, by selling a wider variety of comics and by getting into non-comics merchandise that helped stores to stay in business.

“It was fun,” he said. “You know, I loved coming to work every day.”

And the people from the early days at Capital City remain in touch.

“I still see Milton on a regular basis,” Davis said. “We’re still good friends. Tom Flinn and I are still playing music together. We had a gig a couple of weeks ago. So some things don’t change.”

Source: ICv2