Bill Schanes was just 13 when he and his brother, 17-year-old Steve, started selling comics almost by accident. What started out as a small business run out of the brothers’ bedroom grew into four comic shops in San Diego and then into a full-fledged distributorship, and eventually a publisher as well. Part 1 of this interview focuses on the beginning of Schanes’ career, from casually buying and selling comics with his brother Steve to opening their store, Pacific Comics. In Part 2 he talks about growing Pacific Comics and moving toward distribution, as well as the state of comics retailing in San Diego and Los Angeles in the 1970s. Part 3 is Schanes’ account of moving to direct distribution and making his first deals with Marvel Comics and DC Comics while still in his teens.

To watch a video of this interview, see “ICv2 Video Interview – Bill Schanes.”

This interview and article are part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see “Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary.”

I’m here with Bill Schanes, who’s had a long career in the comics business and a big role in the development of the direct market. We’re going to be talking today about the early days and how direct distribution made it possible for his business to grow in the early days.

Let’s start out with your earliest retailing experience. When did you first start selling comics?

In 1971, my brother was 17, I was 13. We rode our bicycles to a local flea market, like a swap meet or flea market. There was a lady in there that had an old surfer van with surf boards on both sides, like a rack, and then in front of her stall, she had boxes and boxes of comics.

This is San Diego, correct?

Yes. We had never seen comics before. We didn’t know what they were. I’m on, unfortunately, the extreme high level of dyslexia, so I was having real trouble reading anything. In fact, to this day, I’ve never read a book or a novel. It’s just too difficult for me.

When we saw these comics, I sat down and started reading them right away. The eye was tracking the words and the pictures and, for the first time, I was actually understanding a story. For me, it was almost an educational breakthrough versus a comic book fantasy land.

She wanted $50 for about 1,000 books, so five cents each. Cover price back then was 10 cents, so it was a little bit cheaper than cover price, half, but we didn’t have $50 between the two of us. We asked the lady to hold them for an hour. If we’re not back in an hour, sell them. We rode our bikes back to my parent’s house and asked my mother to give us $50, which for a teacher—my mother was a teacher—was a huge amount of money in 1971.

I said, “Mom, I read like four or five, and I loved them. I get the stories. I want to read more.” That convinced her that was a good thing. She loaned us the $50. She drove us down in our family station wagon because we couldn’t pick the comics up on our bicycles.

We bought about 1,000 comics, $50, brought them home. We didn’t know anything about comics. We didn’t know publisher names, titles, issue numbers, artists. We knew nothing. You think about 1,000 comics, 1971, most of them were Silver Age or early Golden Age, but we didn’t know there was Silver Age, Golden age, anything. There was tonnage.

We’re getting home, and we’re unpacking the car, my mom’s station wagon, and my best friend who was a closet comic book collector but never told me he was a comic book collector, saw us unloading comics and came over and said, “Hey, I want to buy that Fantastic Four #2.”

I said, “What’s a Fantastic Four, and what’s a number two?” I didn’t know. I didn’t know what Marvel Comics is. He was explaining to me what’s going on. said, “I can’t sell anything until I read them,” I said. “I want to read them all, but after I finish reading it, I’ll sell it to you. How much will you pay me for it?” I figured, I’d just paid five cents each. He said, “I’ll pay you $38.” In my mind, $50 for 1,000, $12 for 999, I can make that work.

So literally, our first day of business was the collection at the swap meet, and then a friend introduced me the next week to all the Comic‑Con early founders and members, Richard Alf, Mike Towry, Shel Dorf, and they all came over the next weekend, and about 15 other people came over. They dropped like $1,000. We didn’t know what they were buying. We had no idea what valuations. None of them were sorted alphabetically, we just were reading them as we were reading them.

We’re like, “OK, we paid our parents back $50. That was a good deal.” We had cash, and we had most of the comics left over. They were cherry‑picking, clearly, the better ones, whatever they wanted. I wish I knew the list. I wish I knew what that was, because in 1971, 1,000 comics, and there’s no duplicates, that was a pretty good run. That was a pretty good set of comics. There must have been some real good cherries in there.

How did they know what they were worth? How did your friend know Fantastic Four #2 was worth $38?

I think the Overstreet Price Guide had just come out, and the Comic Buyer’s Guide was already out by a few years, I think about a year and a half or two years, so I think the hardcore collectors knew there were trading values out there.

Plus, these were all San Diego Comic‑Con people. They had done the first show, the dealer’s room. They were buying and selling in the dealer’s room, so they had some expertise, whatever that meant in 1971. They had some knowledge.

The next week, we did about $1,000, and then we realized this is a good thing for us to do. We were still going to school, of course. I was 13. We started, every weekend, people were at our house buying stuff.

It was a crazy—mostly bicycles piled up on the sidewalk outside, because most of the fans back then, early Comic‑Con people, weren’t old enough to drive cars. They all drove bicycles. We didn’t have a bike rack, just a pile of bicycles in front of the house. At first, my parents thought it was pretty cute. It was fun. It was keeping us active, and I was reading, which was a very good thing. Then it got kind of annoying pretty quickly because every weekend, there was 20, 30 people, every weekend.

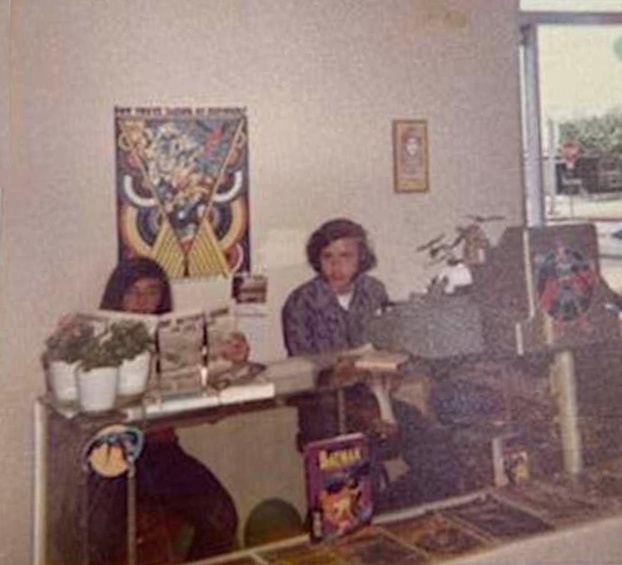

We had a swimming pool in the back of our house. My parents had converted the garage to two bedrooms. My brother Steve and myself had built shelves from floor to ceiling on three walls in both bedrooms to store more comics. The bed was right in the middle of the room, so we were surrounded by comic book racks, basically, or shelving units.

The kids would start off in our bedrooms buying and trading stuff. They’d bring comics with them too, to trade. We quickly learned there was the Overstreet Price Guide, and there was different evaluations out there. We got a subscription to CBG. We were trying to get in the know pretty quickly.

You mentioned Richard Alf, who I remember from the back pages of comics. Was he a dealer then?

Yes, and he was also one of the founders of San Diego Comic‑Con. He had put up, I think, a couple thousand dollars. He was a high school student, and he financed the first Comic‑Con with Shel Dorf and a few other people. Shel Dorf had started off in early fandom at the Detroit Triple Fan Fair. And Ken Krueger started off in the 1930s or 1940s at the World Science Fiction Conventions.

Ken Krueger, who I knew well. He worked for Capital City Distribution and Pacific. A really great man, an important man in comic history, for sure.

He’s a very funky guy, but boy, he could really charm you in his own unique way, that cigar‑smoking non‑stop. He had a lot of internal knowledge, and he seemed to want to share it with kids in the best of ways.

These people would come over to our house. Our parents were getting pretty frustrated. After like a year, “We can’t take it anymore.” Sometimes there were 50 people roaming around.

They wouldn’t stop at our bedrooms. They’d be swimming. They’d be going in other bedrooms, raiding the refrigerator. It was chaos. I think in ’72 or ’73, we had some of the Comic‑Con convention committee meetings at our house. The committee members knew they could buy and sell afterwards and then go swimming. They get three things for one meeting.

Then my parents basically said, “This is getting to be too much. You gotta move out with the stuff. You can stay, but the inventory’s gotta go.” We were buying at a very rapid pace. We were like a vacuum cleaner. If there was a collection available, we were gobbling it up in huge…

Where were you finding comics?

There was a lot of collections in Southern California.

Flea markets, those kind of places?

Yes, garage sales. There’s a famous golden‑age collector family called the Carters, Gary and Laine Carter out on Coronado Island, who was one of the first people to amass the complete DC collection. They sold us about 2,000 comics of their secondary condition copies.

They had a Superman #25, let’s say, that back then, before the Mile High Collection, the Edgar Church Collection was found, was considered very good. Obviously, after the Edgar Church collection was found by Chuck Rozanski, it would have been a poor collection at best. It set a new bar for quality control.

They sold us a lot of comics for about $1,000. It was their leftover Golden Age and Silver Age, because they already had a better copy now. Laine and Gary Carter and their father had this immense collection in Coronado. They were always buying bulk stuff, and every time they got a duplicate, they just called and said, “I got too many of these.” They were not full retail, but not wholesale, kind of in‑between.

They were shoveling stuff our way for a long time, along with garage sales, swap meets. We ran little newspaper ads in the classifieds. The free paper out here is called The Reader. It’s a giveaway every week. We ran little ads in The Reader saying we buy old comics. People would just call and sell us stuff.

You weren’t buying any new comics at this point, right?

Not really. We might have been buying some off a 7‑Eleven rack to read. We realized now numbering and issues had meaning, and we had 1, 2, 4, 7, 9, and number 10 just came out. If we wanted to continue the storyline or continue the reading, we had to cough up the 25 cents or 10 cents, whatever it was back then.

So, you had to get your stuff out of the house. Is that when you opened your first store?

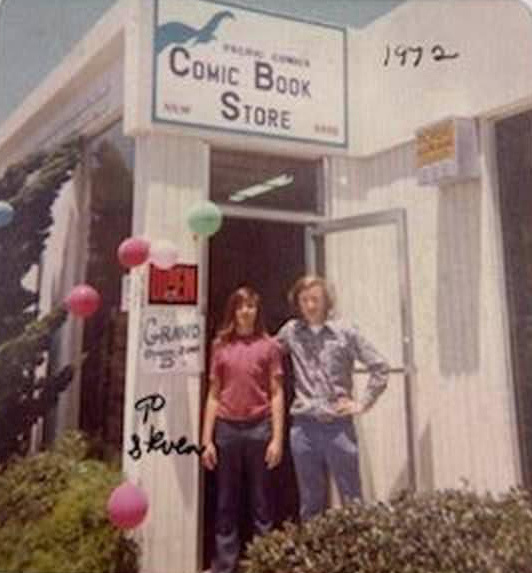

Yes, we found a store about a mile and a half from our house in Pacific Beach. Our parents were in Pacific Beach as well, thus Pacific Comics, Pacific Beach. It was about a mile and a half from my house, easy bicycle ride because we couldn’t drive back then. It was also very close to the beach, about half a mile, so I could go surfing either before it opened or after it closed.

Nice.

That was an important location. We weren’t shopping for location, location, location. We were shopping for cheapest rent possible, and the side benefit was the beach was close.

That’s a very Southern California kind of retailing experience.

It’s pretty ridiculous. The little strip mall we were in, there was a dog‑grooming place on one side of us and then an old‑fashioned run‑down bar on the other side. Clearly, this was not location, location, location. The bar had drunks coming in all day long. They were drunk before they got there, and they were more drunk when they left.

On the other side of our wall, all we could hear was dogs yelping as they’re getting a haircut, they’re getting groomed. We’re hearing yip, yip, yip in the background, which was driving us crazy. The bar guy was getting so concerned about his drunk customers leaving the bar and maybe walking to our store, he installed a doorbell next to our cash wrap. If we had any trouble, we’d push the doorbell, he’d come over and get the drunk out.

Oh, nice.

One day, a drunk did come in, in our early years, and broke two or three of our showcases, just put his fist through them, and then punched me in the face once and knocked out two teeth. I pressed the doorbell, and the bar guy came over and beat the crap out of the guy, just pummeled him.

He was gone in two minutes. The guy just kept pounding him to make a mark. I was pretty much out of it, but he was not stopping hitting this poor guy. We learned early that a security system is probably a good idea.

Was Steve 18 at that point? Were either of you 18?

He would have been 18 or 19.

So you were legal adults and could operate a store and sign things and so on?

Well, sometimes, we had to get our parents to sign. When we put our first catalog out—after that swap meet, we put a catalog out—we didn’t know you had to have multiple copies of an item to list it. We had this thousand‑book collection. We put the catalog out. Some books had been sold from local sales to local Comic‑Con people. And we got a huge response from the mail‑order catalog, like hundreds and hundreds of orders the first week. We had one of everything. We spent more time writing refund checks than filling orders because the first order in wiped us out. We didn’t realize you had to have more than one. We had no education or knowledge about how inventory worked.

And in reality, when we got this money in, we’re getting, from mail order, mostly quarters, dimes, nickels, and dollar bills. Almost no one wrote checks. Our postman hated us because the mail was heavy. Half the envelopes were breaking open, so some of the change had been lost in the mail, and then we end up with bags of coins, literally like Uncle Scrooge bags of coins.

I had driven my bicycle down to Crocker National Bank, the big West Coast bank back then. I wanted to open an account to get rid of these coins. The bank manager said, “Well, you can’t have an account. You’re not of legal age. You have to have your patients cosign.” It pissed me off. I said, “I got cash. You’re a bank. I want to put my cash in your bank.” He would not give.

I rode my bike back to the house and got my mom to drive me back down. She was very supportive because I was—not handicapped from my reading disabilities, but I was challenged. My mom knew she had to invest in me in every way possible to keep me from drowning in illiteracy issues.

She sat down at the same bank, said, “Look, he wants to open an account by himself. He’s a young man,” probably 14 at that point. The bank’s like, “No, can’t do it. You have to cosign.”

“He’s not going to cosign. I’m not cosigning.” She asked for the manager to come over. The manager came over. I had my two bags of coins. He said, “Open the kid up.” I got a bank account for Steve and myself. Ironically, as I was leaving, the bank manager gave me a teddy bear. Called a Crocker Bear. I’m like, “What is this bear for? Why are you giving me a bear? You’re a bank. I don’t understand it.” He says, “All new accounts get a teddy bear.” It doesn’t even say Crocker Bank on it. I said, “Well, I don’t understand why you’re giving me a teddy bear. Why don’t you give me a Crocker Spaniel and have on the jacket, ‘Crocker National Bank’?”

Two months later, they gave out Crocker Spaniels West Coast-wide. The teddy bears were gone. Never got any credit. I got no byline. I got no money for it, but I thought it was a much better name for a giveaway item than a teddy bear.

For Part 2 of this interview, click here.

Source: ICv2