Comic and graphic novel sales have been declining in 2023, leading some to fear for the survival of the medium. The current round of discussion started with retailer Phil Boyle’s recent column (see “It’s Nearly 2024 and I’m More than Concerned“). He argues that as “comic sales find new lows,” Marvel and DC have “gutted an army of passionate retailers.” He attributes sales declines to “false bolstering of numbers through variant covers, convoluted events, and incessant reboots,” and “character swapping, gender-bending, and changing sexual orientation of beloved characters.”

Boyle also notes abuse of the FOC system, requiring retailers to FOC an issue two issues out, and highly variable variant programs that increase risk and make it harder to predict sales, a big problem for a channel that has to order most comics non-returnable.

He suggests that the Direct Market has “TWO years tops” without major interventions, including lower-priced comics, fewer covers, better editing, fewer character changes, and higher discounts for comic stores, among other suggestions.

A couple of days later, Mark Millar jumped in on Twitter, bemoaning low sales on comics from the Big Two, and also suggesting that “the Direct Market is a couple of years away from complete collapse.”

Millar notes that Big Two page rates for artists are a “FRACTION of what my peers and I earned on those titles 15 years ago,” plus a “2% royalty on sales over, broadly speaking, 50,000 sales.” Almost no titles are selling over 50,000 copies an issue, he says, making even that royalty percentage moot. He suggests a much higher royalty rate on sales over 60,000 copies, incentivizing top creators to work on top books because of the potential for much higher royalty payments.

They’re both really talking about two things: the survival of superhero comics from Marvel and DC, and the survival of comic stores. Those two things have been strongly linked historically, but don’t have to be.

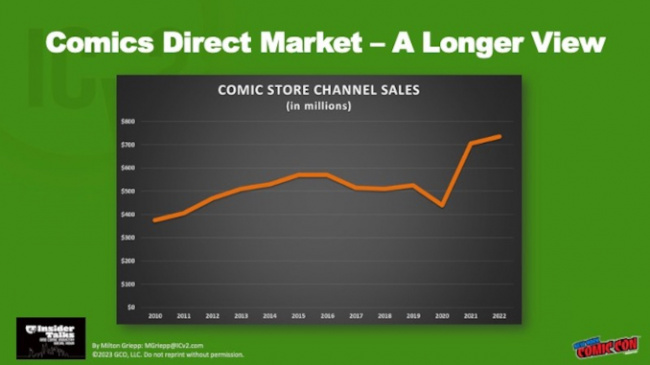

I took a look at what’s been happening in the Direct Market since 2010 for my presentation at the ICv2 Insider Talks at New York Comic Con, and the big picture of sales in comic stores in that period is encouraging: sales nearly doubled during a time span when the broadest measure of inflation was 41%. But by format, there was a big divergence: all the growth in comic stores relative to inflation was in graphic novels. Inflation between 2010 and 2022 was 41%; comic book sales in the Direct Market were up 40%, and graphic novel sales in the channel roughly 4.6 times as large in 2022 as they were in 2010 (see “ICv2 Insider Talks: Direct Market Trends“).

What’s going on with superhero comics? The decline in periodical sales is related to a decline in the popularity of superheroes as a genre of comics. We do regular analyses of graphic novel dollar sales across both the book channel and comic store channel, and superhero graphic novels (which we define as corporate-owned content, i.e., Marvels and DCs, and licensed comics tied to movies, TV shows, etc.) represented about 14% of all graphic novel sales in 2022. That’s tied with what we call “Author” graphic novels (creator-owned works), and lags Kids graphic novels (26%) and manga (45%) (see “Video and Slide Deck: ICv2 White Paper 2023“).

Validating the sales decline, our analysis, based on numbers from stores using the ComicHub POS system, shows both comics and graphic novel sales in comic stores down 7% through August 2023, although conditions may have worsened since then.

Prices are higher, but if people really wanted the comics with high prices, they’d pay the price and buy the comic. And all the other reasons why people might not be buying superhero comics (competition from social media, from streaming, from anything else people can do with their time and money) are true in other countries or at other times correlated with better comic sales.

I’ve been in the comics business for more decades than I care to enumerate, and I tell you with absolute certainty: It’s always what’s between the covers.

So what’s going on between the covers? Boyle listed a number of specific issues with Marvel and DC content, some political, but I don’t buy that most of them are critical, and some of them don’t matter at all. Good stories about gay characters sell, good stories about female superheroes sell, good stories about black or Latino superheroes sell.

I think there’s a very general reason why Marvels and DCs aren’t selling: they aren’t very good.

I had a rule when I was in distribution, and it was “good is as good sells.” That means the definition of a good product is that when you expose it to an audience it sells. That’s not happening with Marvels and DCs, so by definition, they’re not very good.

The “why” is a bigger question, with a lot of theories. First of all, it’s hard to produce great comics, or any kind of great entertainment. If it were easy, they’d all be great, and we’d all be rich. There are some periods when the industry is on fire, with creativity pouring out of every pore (see “Why 1986 Stands Out as a High Water Mark for the Direct Market Era“). At other times, even though everybody’s trying, the results are poor. So one theory is that we’re just in a weak period creatively, for reasons that we’ll never understand.

Another theory is that people are getting their superhero fix from big-budget movies and TV shows, and have superhero fatigue; they’re just sick of the genre, or don’t want any more than what they can get on a screen.

I suspect there’s more to it than the answers either of those theories provide.

The talent migration away from the Big Two has been dramatic over the last decade, related to compensation and rights, with the situation now in a spiral in which lower sales produce lower compensation for comic creators, which causes good talent to leave, which lowers sales, and so on.

As one tiny example, over the past weekend, I started watching Monarch: Legacy of Monsters, the new Apple TV+ Legendary series set in their Monsterverse, where Godzilla and other monsters live in a transmedia universe spanning movies and television (see “Monsterverse Title, Date“). The series has an 85% Tomatometer rating, and a 90% audience score. It’s co-created by Matt Fraction. Remember him? He created the bestselling Hawkeye series for Marvel (and a bunch of others), which sold well as periodicals and then sat near the top of the superhero graphic novel bestseller charts across channels for months. The first issue from roughly 10 years ago sells for $45 in VF+ at MyComicShop. Fraction is doing something else now.

Even creators that have stayed in comics have migrated from the Big Two to publishers where they get more creative freedom and the chance to cash in at megabucks level if their property gets picked up for a TV series or a movie.

This is a solvable problem, but it involves financial and creative risk for the Big Two: they could compensate top creators in ways that make them want to do books featuring their most popular superhero characters, and give them the freedom to play in those sandboxes in ways that reward them creatively.

Another rule of thumb from my years of experience is that there’s always a number, and I’m sure there is a deal out there that could bring top talent to top books. Do the massive entertainment conglomerates that own Marvel and DC care enough about comics to authorize that risk? We can only hope that the pain of what they’re experiencing in those divisions now, and the massive upside they could reap from great stories that start in comics but can also be told in other media, brings them to their senses.

On the retail side, I am more optimistic about the future of comic stores than either Boyle or Millar, even if the Big Two don’t get their acts together any time soon. I think Direct Market retailers can adapt to the market as it exists, retaining what’s working for them in the periodical business, while expanding their sales of manga, webtoon collections, kids graphic novels, and OGNs. They can continue to win customers based on their curation (although it may involve fewer superheroes), and on the authenticity that selling periodicals imparts to the store experience. They can build community around creators and shared tastes, and nurture a devoted customer base. And they can carry products from adjacent verticals to smooth their sales from comics (games, anyone?).

It’s a big change in emphasis, and I don’t underestimate the difficulty for retailers in building up parts of their businesses that haven’t been as key until now. But I also believe that comic retailers are among the smartest, hardest-working businesspeople in the comics ecosystem, and that their closeness to their customers and their product can be their salvation. If they made it through a global pandemic, they can make it through a creative dry spell from Marvel and DC, especially with a little help from the publishers, distributors, and others that make money in the Direct Market. More on that in a future column.

For more on the Direct Market on its 50th anniversary, see “Direct Market 50th Anniversary.”

Got thoughts on this topic? Send in your comments for potential publication to Comments@ICv2.com.

Source: ICv2