For this part of the history of the Direct Market, we are turning the tables and letting comics historian Dan Gearino, writer of Comic Shop: The Retail Mavericks Who Gave Us a New Geek Culture, interview ICv2 CEO Milton Griepp about his days at the helm of Capital City Distribution. Griepp and his partner John Davis started Capital City in 1980, and it grew from, literally, two guys and a truck to become the largest comics distributor in the U.S. In Part 2, Griepp describes Capital City’s years of growth, starting with just him, Davis, and a battered truck and growing to a nationwide organization with over 700 employees. Part 1 focuses on Griepp’s early days working for a Wisconsin distributor of alternative papers and underground comics that was swallowed up by a larger distributor with a very different culture and ultimately went bankrupt, leaving him and Davis to strike out on their own and create Capital City. And in Part 3, Griepp talks about Marvel’s decision to self-distribute and the chain reaction that started, which ultimately led him and Davis to sell Capital City to Diamond in 1996.

To watch a video of this interview, see “ICv2 Video Interview – Milton Griepp, Part 2.”

This interview and article are part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see “Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary.”

Dan Gearino: How many months into the existence of Capital City did you hire an employee?

Milton Griepp: I don’t think it was the first year. It was probably the second year.

Give me an idea. Year Zero, it’s just the two co‑founders. Year One, you’re adding one person. Because you’re getting into this period soon after that, where you guys just start growing like crazy. Around what year do we go into that, I don’t know if you’d call it a middle period, but that growth period where things just started changing quickly.

First, just to set the stage for that first year, it was so quiet that there were times we didn’t have anything to do. After we packed the comics, the next comics weren’t coming in for a while. If it wasn’t that week of the month when we had to collect orders, we’d have beach days and go to the beach.

There wasn’t a lot going on at the beginning, and then it just kept incrementally getting bigger. I think those first three years we tripled every year. I think our first year in business, we did $250,000 in sales. The second year was $750,000. The third year was $2.25 million. The growth started pretty quickly after that first year.

What was the source of that growth? I’m going to assume that your customers were selling more just in their own shops, but you’re also adding stores. Were you expanding geographically or how would you describe the nature of that growth?

We were always working hard at reestablishing ties that we’d had at Big Rapids or establishing new ties. The way we did that was by going to conventions. We’d go to conventions in Chicago. We went to San Diego Comic-Con. Everywhere we went, we’d try to find new suppliers that we weren’t doing business with initially and also find new customers. It was geographic growth, word of mouth, and really conventions were the way that we found comic stores.

You’re talking about those first three years of growth. Is that, in your mind, the demarcation, where you’re on the launch pad and things got really big after that? Around when do you think you go from that very small shop, where it’s a very intimate group, to just, you’re taking off like a rocket ship?

After that third year, I remember sitting down and doing the math. Gee, if we can triple every year for like however many years it was, we’d be a billion‑dollar company. That growth rate cannot be sustained on larger numbers, sadly. The growth rate did slow, but we were adding millions of dollars in sales every year.

There were years when it was very tough, when the market would suddenly become less responsive to certain kinds of inventory. Inventory would pile up at the stores, they’d have trouble paying us, inventory would pile up at our place, we’d have to cut inventory, run sales, move inventory through.

It wasn’t a straight line at all, but there was definitely continuous underlying growth of the consumers that were shopping in comic stores, and the number of comic stores was blowing up. It was growing very rapidly.

One of the big crises in the market early in your existence was the black and white bust, right?

Yes.

As a distributor, did that harm you financially?

Sure. There were a couple of busts. I don’t have the years, they were both in the ’80s, one of them was the black and white bust that you alluded to. There was another one on high priced expensive format books. There was a huge expansion in the number of up‑priced books once comic publishers figured out that they could sell comics on better paper for higher prices to the comic stores. Same kind of situation: Everybody ordered a lot, the supply exceeded the demand, inventory piled up at stores, inventory piled up at Capital City. We had to dump inventory. We had to collect money. We had to write off bad debt and keep moving through. Each of those situations required rapid adjustment or we would have died like some of our colleagues did.

Rapid adjustment? What does that mean?

It means you stop ordering as much, you cut your orders, order right to the bone, very close to pre-orders rather than having extras to sell reorders. You look at receivables more aggressively. If somebody’s not paying, you don’t give them as much rope. You tighten up the receivables.

You look at expenses—what can I do to manage expenses more effectively?—which in a lot of cases was beneficial because it would help us become more efficient as we tried to figure out cheaper ways to do things.

We’re getting into an era here where some of the things that I think of when I think of Capital City are these really cool publications. How did that start? You had Internal Correspondence. Walk me through the publications you had and how you got started doing those.

The first thing was that one‑page order form, and so the next phase was something we called Order Pak. That was black and white. It had a stiff cardstock cover, black and white, and a newsprint interior. That included images of some comics. It included a longer description, so there was some indication of what was going on in the plots.

At that point we went to soliciting orders for each issue of Media Scene or Comics Reader or Comics Journal or whatever the publication was rather than using standing draws. We did that for a number of years. We always tried to stay ahead.

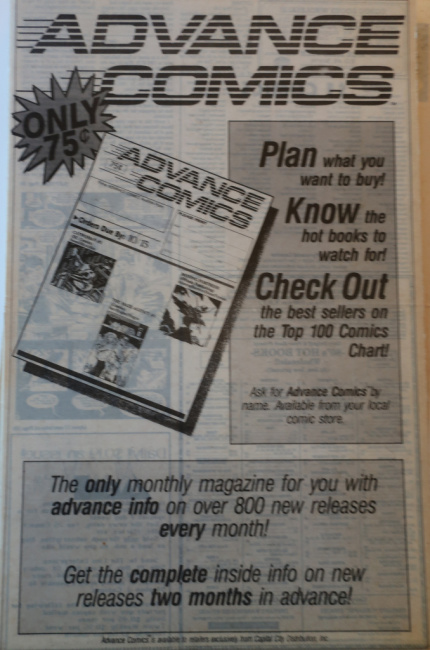

John had published a magazine in the past, Velvet Lightrap Review of Cinema, with Tom Flinn, our first employee. He knew something about magazine production. The pair of us, we were both interested in having something that was aesthetically cool and showed how cool the stuff we were selling was, because we both loved the medium and all this pop culture stuff that is adjacent, and we wanted to present that in a way that people could see how cool it was. We did that Order Pak for a number of years. It got fatter and fatter and then, eventually, in the late ’80s, came up with the idea for a consumer catalog that our stores could use to collect orders before they gave them to us, so a multi‑tier ordering tool. That was Advance Comics.

It was Advance Comics, and you were the first to do this on that scale, right?

We were the first distributor to do a consumer catalog.

When did you start producing Internal Correspondence?

We started running a page of Internal Correspondence‑type news in other publications. I think it was maybe in OrderPak at first. We did a weekly that was just stapled pieces of paper that listed all the products that came out that week, and we would have “Internal Correspondence news” in that. As a separate publication, it was the mid‑80s, sometime.

The name, by the way, came from, Marvel used to send out these memos which were internal correspondence to Marvel but they would send to their distributors. It was like, “Internal Correspondence, new title launching June,” and then they’d have information about the title.

We thought that was cool, the idea of you being able to see the internal memos or correspondence of the company that you’re interested in, we’ll use that for our title.

I remember just looking at some of that stuff. A t times, with Internal Correspondence, I’m thinking, man, these guys are in the wrong business. They should just be publishing magazines. This is a really cool publication. Of course, that’s another business that’s incredibly challenging.

I want to make sure not to skip over the move to air freight. Your company was growing like crazy, and you’re growing into different regions across the country. Were you the first to do air freight, or how did that work?

I think it was Russ Ernst, Glenwood, which is that company based in Collinsville, Illinois, close to the printer that I mentioned. I think that even went back to the late ’70s, because I remember I went to Los Angeles with Kennedy, and I think there was one other person on that trip. It might have been Kwant, Pete Kwant. We were selling to this newsstand at Hollywood and Cahuenga in Los Angeles. It’s known as World Book & News. It’s world famous. It’s 24/7, 365 days a year newsstand. Every magazine ever printed. Huge pornography section. Mass market paperbacks. This guy that owned it, his name was Bernie Weisman and he had a house in Woodland Hills because that was a very profitable store.

I remember him on that trip talking about “Punks! Peddling comics! Out of the trunks of their cars!” He was talking about these sub-distributors that Russ Ernst had in the Los Angeles area that literally bought comics from him, he sent them in air freight and then they would drive from store to store with comics in the trunks of their cars.

I think it started then. It had been going on for a while from Glenwood.

Was Capital City a company that substantially increased the use of air freight or did air freight on a much larger scale than had been done before in the mid‑’80s? As you know, there’s this period among the competition, among distributors that they call the Air Freight Wars where different distributors are flying stuff in at great cost to get their comics to their stores sooner. What was Capital City’s role in that?

First of all, I’d just set the stage by saying that logistics was a huge part of the competitive environment in that era. There were no street dates. Comics came out of World Color Press at midnight on, I think it was Wednesday night then. The goal was how fast could you get them to stores, because the comic stores that had them first would sell more, because comic fans want to read the next episode of their favorite comics as quickly as possible.

It was a huge part of competition, whether it was with trucks or with air. Increasingly, we were running our own trucks, whether to bring freight in or to deliver to stores, and using third party carriers less and less.

The air freight side of it really came out of we bought Pacific Comics’ Sparta, Illinois, location, or certain assets related to it. That, again, was right next to the printer. So we had the ability to get our hands on the comics very early.

At some point, we had a manager there, Judy Crain, who got to know people at TWA in St. Louis. TWA was hubbed in St. Louis. They flew planes all over the country from there. They had deals for freight containers that would fit in the bottoms of the planes that weren’t maxed out with luggage. They had several sizes. There were these large cardboard things that were a couple of hundred pounds up to much larger containers that fit in the bellies of planes.

We were able to get freight rates down for air freight using this unused capacity in passenger planes to equal to or less than trucking from the Midwest to California, for example. That was a huge differentiation between us and our competitors. Because we had the location in Sparta, we had access to cheap air freight. We started using that to put out comics faster.

About what year was that?

It’s mid‑’80s sometime.

It may have been a matter of Capital City coming up with a better and a cost‑effective way to serve its customers, but as you know, Bud Plant and his company, they looked at the fact that you could get your stuff to your customers quicker. It was like creating this need where then they felt like they had to do air freight, which they thought was wasteful, or they thought was not cost‑effective.

Was it more than just Bud’s company? What were the main competitors that eventually got in air freight?

Well, our third location was Northern California, Bay Area. That was one of the first places we started doing air freight to a Capital City location. That was a significant change.

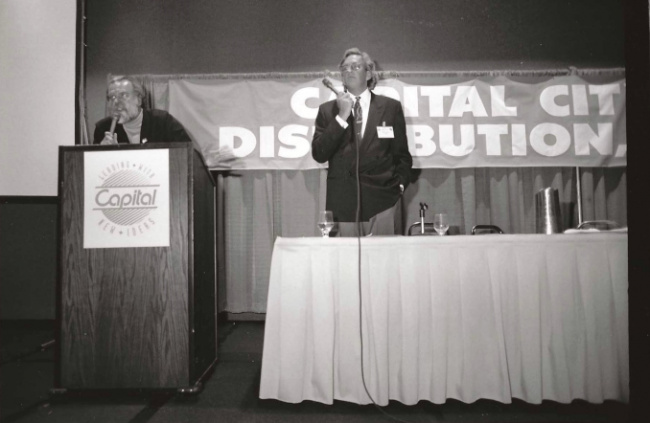

There had been talk at distributor meetings. We had a trade association called IADD, the International Association of Direct Distributors. There was talk at those about, “Gee, air freight is wasteful,” and so on, but the basic tenet of that argument was that air freight was more expensive than truck, and we found a way that that wasn’t the case anymore. We felt that it was no longer wasteful, and it was appropriate to use it to move the freight as quickly as possible.

We started doing that in Northern California. Over time, the typical steps from there on would be to build up a base of customers in an area using air freight, then open a branch to service those customers in that market and air freight the comics in bulk and have them broken locally. There was a few hours between when comics were released at midnight and when they had to go to the airport to catch the first flights. In some cases, we were packing down to the retailer level, and then shipping them out to the branch. In other cases, they packed them locally.

You are a company that is growing a lot. There are all these other companies around the country, but it wasn’t like the independent distributors that had these super firm territories. You were acquiring customers in areas where other people were established. Yet you guys were in this trade association together. It seems like you knew each other. You were friendly. What was that competitive environment like?

It was those two things, that dichotomy. It was tooth and claw. When I was going through some of the old notes and papers and stuff from that period, it was a very crazy period in terms of how competitive it was. Every store was hard fought, tooth and nail. “How can we get this customer? He wants 30 days instead of 15. He needs his books at 11:00 on Thursday.” Whatever was necessary to get the business. We were competing at a very granular level for every single store.

On the other hand, we had common interests, and those common interests were primarily related to the publishers and how they treated us. A lot of it was competition between direct distributors and what was left of the ID wholesalers. For example, we had common interest in ending the corruption of ID wholesalers who were selling comics that they had ostensibly returned and gotten credit for on an affidavit, but then were selling off into the back issue market at a nickel apiece. That wasn’t good for the back issue value of comics, and so we had a common interest in trying to fight that.

Timing of deliveries, things like having the publishers subsidize our trucks rather than ship comics to us using third party carriers that were slower. A rack program was one of the big things. I worked very hard on that at the association. I think I was maybe vice president or something by then. The goal was, can we get the publishers to share in the cost of racks for stores, just as they did for stores serviced by the ID wholesaler network?

There were a lot of common interests. It was a very rapidly growing segment and channel. We had competitive issues with other channels. We worked together on those. There was definitely a collegiality, because we had the same things, “Oh, so and so burned me. Did he burn you too?”

We were dealing with the same stores, in a lot of cases, the same suppliers, and we had a lot in common.

We get to a point where you guys, Capital City became the largest distributor in the country for a chunk of time, right?

Yes.

Then you’ve got Diamond, which is rapidly growing, based in the Baltimore area. You’ve got Bud Plant. Would Bud Plant have been the third biggest, or was there someone else that was bigger in the late ’80s?

I’m not sure. They were big because they’d picked up the bones of Pacific and the West Coast. California is, whatever, 10% of the market. They had most of that. They were sub‑distributing in Denver. They were selling in Arizona. So the western part of the country, they had a very large share. I’m guessing they were probably third.

We’ll get back in just a minute to some of the back and forth of competitive issues with the different distributors, but I’m wondering what’s going on in your company culture at this time. You guys have just grown so much. You started out as, like you said, two guys who even drove the trucks, and you were becoming gigantic. A bunch of your good friends are working in the company and were there from the very beginning, but you also added a ton of people. Was there a point when Capital City just fundamentally became a different company just because it was so big?

Those changes were incremental, and I think the biggest thing we did that helped us grow and be successful for so long was acquiring expertise, either through training of ourselves and our employees, or hiring experts in different areas.

The internal training for example, I think the years were probably late ’80s, early ’90s, I got involved with the American Management Association, which ran a lot of training programs. I went to their President’s School, which was a week-long program that taught people that were running companies how to do things. I took a lot of human resources seminars. Really worked on getting better at our jobs. I personally worked very hard at getting better at my job. And then we would bring in training. We had American Management Association consultants help us build an internal strategic planning process. Here’s how you go through the planning process. Here’s how it relates to budgeting. I hired two accountants to run different aspects of the financial parts of the company. We had good CPA advice, and they were excellent and good at their jobs and helped us evolve. They built strong staffs, which helped us.

I really became hugely appreciative of the accounting profession, because you could run a business based on the information they generated, and you couldn’t run it if you didn’t know what the hell was going on. That was really important.

We hired people that were trained purchasing people, and we also were very early at trying to incorporate computers into our operations. I think we had our first computer in 1982. The brand was Superbrain and it ran on a pre‑DOS operating system. That’s how long ago it was. Two 64K floppy drives were the entire memory of the device. One was for software and one was for your data. That built up over time, and eventually, in the early ’90s, we hired Ernst and Young to come in and help us develop a much more elaborate and powerful computer system that ran on the IBM AS400, which is a minicomputer, with T1 lines connecting the locations.

All of those changes helped us run the business much more effectively. I remember when I started seeing the data come in so rapidly with these connections to the branches and a single computer that accumulated all that information and presented it. It was like turning on a light in a dark room. I’d only been seeing half of what was going on before that, and suddenly there was all this information available. We had to change very rapidly. If we hadn’t, we wouldn’t have been successful.

In talking to some of the other people who were longtime employees there (these are all people you’re in touch with, and obviously everyone’s still friends), they say that as it grew, it was super entrepreneurial, friendly, like going to work with your pals, and then it became big business later on. They said it became a little less fun along the line. How did you feel? Is that just what has to happen to continue growing? What do you think?

I would say part of that was getting better at human resources. One of the big things I came to understand as the person running the company is that every action I took was important. Somebody was always watching and interpreting what I was doing and applying it to their own jobs and how they interacted with people. If I did something that showed disrespect for a customer or disrespect for an employee, that would come back, and it would be felt in the culture. I had to manage how I interacted with people in every instance, so that the people around me could take the right example from that.

That meant being more rigid, in the sense that I couldn’t say things that I might have said in a less guarded moment or behave in ways that were more impetuous. In a way that was difficult, because it meant distancing myself on a personal basis from friends, but it was necessary because otherwise the company would not have been able to function as a business well.

That was a big change. It happened over time. It was incremental. Part of it also, I’ve talked about our advisors. We had a really excellent employment law and labor attorney. He advised me a lot on how to manage employees and how to do things in a way that people saw as fair, which is so, so important when you’re dealing with employees. Those kinds of things meant you can’t favor a friend. You have to deal with everybody the same way. Y ou have to create rules and systems and apply those rules and systems, and that means you’ve got a framework. You’re not just doing it all off the cuff.

You and John, you guys are both running the company throughout the history of the company. What’s it like to be a co‑founder? I would think your relationship with your co‑founder is important. Were you at the point where Capital City was as big as it got to be? Were you guys interacting on a daily basis, or were you off in your own parts of the company doing your thing, or how would you describe your relationship?

We shared an office through the entire history of the company. We built a big new building in ’92, ’93, and created an office there that we could share. We consulted constantly daily, beyond daily, and that was very valuable.

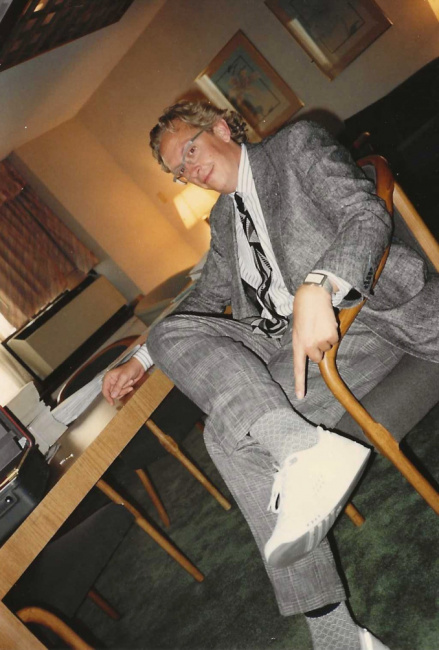

Initially, John was CEO. He was older than I was. He is nine years older than I am. I think I was 27 when we started the company, 26, 27, so he was in his mid‑30s and had a little bit of experience running The Velvet Lightrap, so he had some business experience of a sort.

He was CEO for the first couple of years. We had talked about trading off because we were equal partners. Around ’82 or so, I became CEO. After a couple of years, things were going well and we agreed that I would continue in that role, but certainly we consulted on every major decision and a lot of minor ones.

John has very high EQ, and he was excellent with customers and suppliers, those relationships. He would spend a lot of time on the phone talking to, if the salesperson, customer service person was having trouble with a customer, he’d talk to him. He’d work on acquiring new customers. He had a lot of friends in the supplier base also. We worked together very closely. I would say the management in terms of how’s the company structured and all that stuff, I had a bigger role in, but in terms of external relationships, he was very important.

The impression I get is that if there was an issue somewhere, a conflict needed to be defused, that’s the kind of thing you’d dispatch John for. And then if there was a complex business question or a big strategic thing that need to be taken care of, that would be thing you would be [responsible for]. Is that correct?

Yes.

Getting back now to just the competitive balance of all these different companies, there’s a point where Bud Plant sells his company to Diamond. Bud Plant, whose company is called Bud Plant Incorporated, sells his company to Diamond. First of all, did you have any idea Bud was selling? When you heard it was sold, was that the first indication you had that it was for sale?

Yes.

Did you instantaneously have an idea of what that would do to the business or the whole landscape, or did that kind of come into focus later on?

It wasn’t clear, other than the fact that Diamond was instantly bigger than us. That changed everything about our relationship with our suppliers. Whether that would be a successful integration—I give Steve credit, integrating companies that you acquire is not an easy thing, and he was successful at doing that in a way that kept the business profitable. He paid a price that allowed him to do so profitably. That was a great deal for him, and he should get credit for it.

After that, we then enter this, it’s not quite a duopoly because there were other distributors at that point, but we were at a point now (please correct me if I’m wrong) where Capital City and Diamond are these two giants and are now, this is we’re almost in the heavyweight fight portion of this long history of distributors, right? Or how would you describe it?

Yeah, we were both rolling up smaller distributors, and that had started really in the 80s. Our first branch was we acquired Northeastern Ohio News. Tony Isabella, comics writer Tony Isabella, and Dave Barrington had a little company that was distributing comics in the Cleveland area. We bought out their business, hired them, and opened a branch there. That kind of thing was ongoing through the 80s and early 90s. There are huge economies of scale and benefits of scale in distribution. It became more and more difficult for those smaller companies to survive because they were competing with bigger companies that just had more resources to throw at it.

A lot of that was logistics, and it was all based on moving comics quickly, getting them to the stores quickly, and the smaller companies, they couldn’t afford to run their own trucks to the printers like we could. Scale really brought big benefits.

Click here for Part 3.

Source: ICv2